iDocs 2018 day 1 conference notes

I am attending iDocs 2018, a three day event dedicated to the expanding & evolving field of interactive documentary, in Bristol and will be taking notes on the sessions here.

Keynote: The Shoreline - Liz Miller

Liz Miller presents and discusses collaborative interactive documentary project The Shoreline – a storybook for sustainable futures. The shoreline is a site – where the land meets the sea, where excessive development meets the power of nature, and where climate change dramatically impacts lives and ecosystems. The shoreline is a story device; a site to connect human and non-human communities that survive and adapt in one of the most dynamic places on the planet. The shoreline is also a method – a way to challenge boundaries and narratives in addressing climate-disasters.

First interactive was in 1999 - Moles. Made with Flash 1 - could stream 7 secs of video

“If you want to get others to use this medium you need to come to grips with your own story.””

Other projects: Hands On, Going Public: The art of participatory practice.

Hands on: Poly-vocal solutions based approach.

She teaches in class and many students get overwhelmed because many solutions are either individual-based, or out of reach.

‘solis-talgia’: profund sadness we feel when we see familiar landscapes being destroyed

“As an educator I use interactives all the time, and they work.””

Interactivity allows educators to bring together bite-sized content and allow parallel use of it.

When gathering stories, hosted a wordpress site that has now become a forum of exchange for educators

3 ways to navigate the site: first is by chapters (there are six). Second is through a map. 3rd is through a database (topics/strategy toolkit)

Soundscapes are really effective for elementary classrooms.

Can go from stories to the Strategy Toolkit, or to the community where the story is based and use an interactive map to see what the land would be like if sea level rose by up to 6m

Each chapter ends of ‘floodviews’, dystopic visions of what the future would look like.

Also created workshop cards for non-profits and educators - a way to get a ‘playlist’ of content from a trustworthy source.

Intention fo the project:

-

Reach across disciplines and pedagogical levels

-

free and accessible

-

engage with data visualisation

In short: ‘a video textbook for change’

One of the challenges of idocs for social change is that every profile is an opportunity. tension between too much information overwhelming and desire to capture these opportunities. Interactivity / curation is a solution to this tension.

Sequel to The Shore Line: Swampscapes. Bringing in VR and multi-platform storytelling

Q&A

The first iteration was a database. Current version has a lot more curation.

Users got used to the first iteration and was reluctant to change to subsequent versions.

One big lesson: less is more.

Q: Do you start with the money first, or the concept? A: We’re in year 4. I always start with prototypes and small projects. The New Zealand videos I shot 5 years ago. People’s live chnage and left their jobs in the time I was working.

2 years of [video] production and one year doing the interactivity. It was most expensive and difficult part.

People want paths but they don’t want to be constrained by paths.

Q: Would you think of your project as linear or non-linear? A: The way that the story unfolded itself, it really never had a coherent linear film. it was a network film. If there was a film along the way that I wanted to make it would be a film about mangroves.

Early advice: ‘you’re cutting them like short films. you’re not cutting them like internet films.

It’s about entry: you have to start in the middle’

If you start something small, there is going to be a contagion of hope.

I personally don’t believe that interactives do really well on their own. It needs a teacher or someone local to take people through the site. Guides are aboslutely essential.

This site is a catalyst for solutions-based pedagogy. That’s why we’re focusing on the teachers.

Q: How does the interactivity add to that? A: We can’t rely on any one form. Video will work for some people. Maps work really well for others. People learn differently. An interactive site permits all these different ways fo entry. and once you hve the entry you have the pathway for deeper conversation

Discussed why some students opted in and some opted out.

All of the students doing this weren’t in an assigned class. Those you were most engaged felt a sense of mission.

Q: Authorship in a multi-vocal context A: Trying a framework fo ‘common-ing’ Each contributor ‘owns’ their contribution but also provides it on the understanding that they are contributing it to a bigger (common) project.

Innovating the Story

Jamie McRoberts – Bridging cinematic and interactive VR

Ewan Cass-Kavanagh – Technical innovation and multi-vocal stories

Jamie McRoberts (@nidocs)

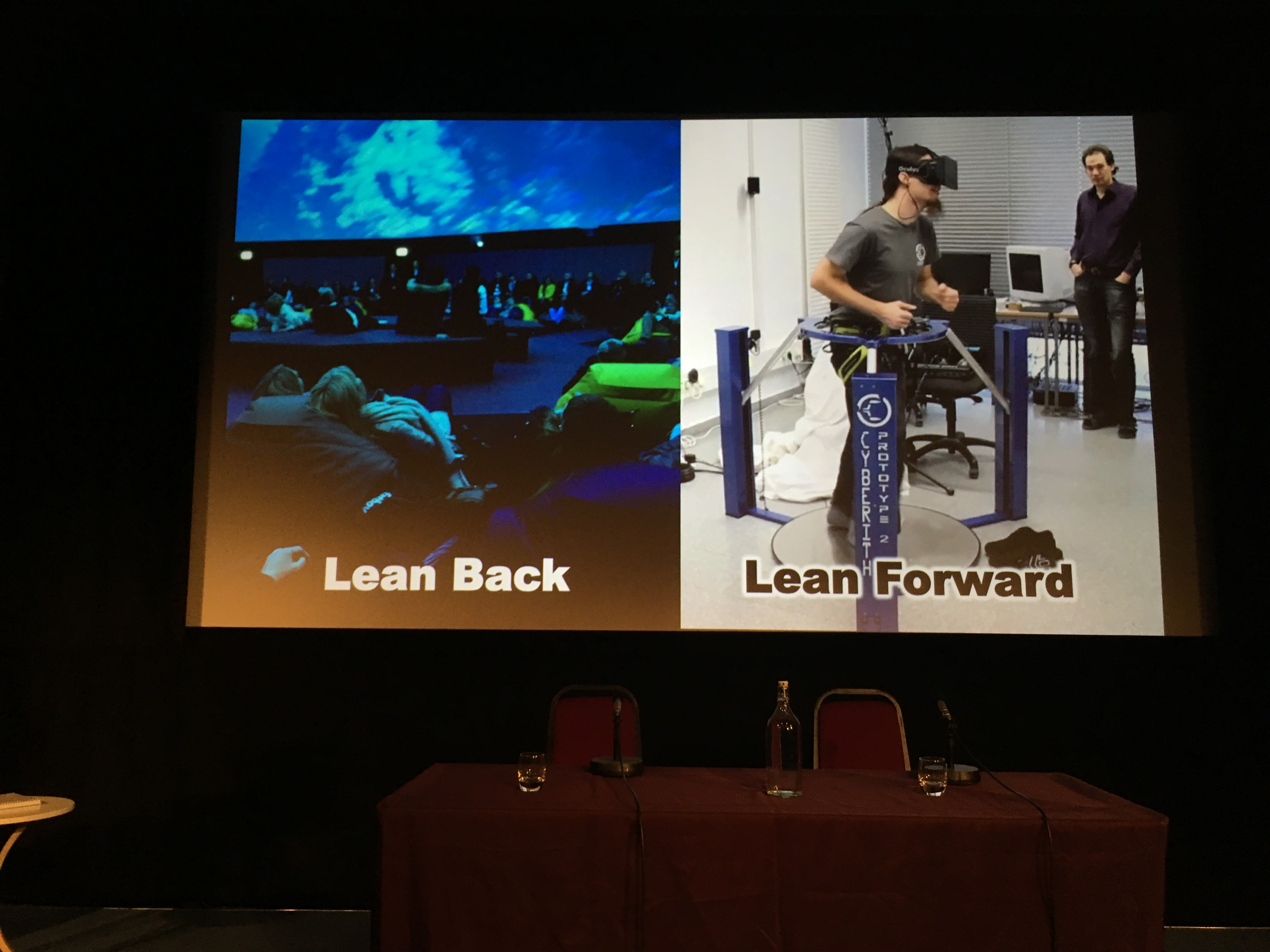

Maze3: Essentially a first-person walkthrough of the site (more info here) and along the way you can access films and text. It was a mix of pixels and polygons, but also two modes of experiences: lean back and lean forward

Some of the challenges of producing cinematic VR: When filming Fight Game VR for the BBC (it’s about boxing), the bouncy canvas of the boxing ring meant had to mount camera on a crane placed outside the ring, which meant had to get rid of the crane in post-production.

One response was people immediately put their hands up and threw some punches themselves. this was interpreted as good because they are immersed, but there was immediately a sense of frustration because their actions weren’t reflected within the VR world.

This raises some questions.

Do we: expect VR audiences to mature and to understand the distinction between cinematic vs interactive VR and the limitations for each

Do we: Consider which content types are suited to cinematic VR and those that are suited to interactivity?

Do we: Experiment in the space between cinematic and interactive forms of VR? Is there a middle ground and what does that look like?

Ewan Cass-Kavanagh (@Ewanck)

Have been working on techniques around multi-vocal sotrytelling. All started with the Quipu project, which is about 300k people who were sterilised in the 90s in Peru

Put in a free phone number that people can call up. when you call, you can either listen to a story or record a story. Recorded 170 testimonies - 8 hours of listening time.

Also allows internet audience to record their responses. Output: 20 min film in Guardian, and built up community locally in Peru.

Why interest in multi-vocal and participatory story-telling?

In this case: it’s intrinsic to the story. each of those people have their own story to tell and the story we’re looking at is the accumulation of their stories. There’s also the beginnings of a political dimension to it. The participatory angle makes these tstories not just about the final results but also the process and the methodology.

Other projects: Anyone’s Child Mexico

Topic that people have strong emotional starting point and established point of view. For example, strong idea that people whose lives are destroyed by drug war are drug-takers. How to inform, create conversration and discussions and empathy in this case?

Similar to Quipu, used free phone line to gather stories. But difference in context - this is still going on in Mexico and people needed to be protected. There’s a controversy around this.

So, while people could call up, this was followed up by in-depth interviews that generated the final pieces. But kept the phone call method because found it to be very powerful. In-depth interviews at low cost from far away. People are used ot it.

Officially launching at end of April in Bristol

Next project: Home 1947 about the Indian partition.

This one is mobile-first design, so you can experience the stories in the same context (the phone) as it’s creation.

Aurator One of the most useful thing was actually creating the back-end content management system for audio was really useful for other people. Also - technology for transcribing

Intercultural Conversations How do you make multi-vocal conversations about hte past?

Quipu: decided to anonymise the archive. This raised the question about agency “A living project has to die” - this is really fundamental. Because while the final output looked simple, there was a lot of work and cost in keeping in running for such a long time. Really important to plan for this and to communicate this clearly from the beginning.

What’s Visible - The Mechanics of i-Docs

Richad Misek (r) on The Hidden Timeline and Adnan Hadzi (front, center) on displaying video as theory and reference system

Richard Misek

How interactivity and linearaity co-exists in moving image, and how this used to be uncomfortable but may now be better resolved.

What do I mean by a timeline? It maps time on to space. it visualises time - giving it a start and end point.

It’s also a metaphor for how cultures understand time.

In its modern form: single axis, regular spacing of points, is only 250 years old. it is an enlightenment invention.

Joseph Priestley’s biography timeline:

Or, a 54-foot long scrolling timeline where the actual object is an actual scroll.

The playbar (i.e. a timeline) has become a default interface for modern media (including films). What’s interesting is that even in many works that embrace interactivity (including i-docs) the timeline keeps coming back.

Example: Bear 71

The entire narrative of Bear 71 is a 20-episode video interspersed with interactivity. It collapses to linearity.

But frame is spatial (the map). There’s a sort of schizophrenic quality as a result.

Exmaple: Filming Revolution

The horizontal timeline of each clip is a frame, but it is itself framed within a non-linear network. It’s a metanym of the internet as a whole.

Are we all caught in the line? Is there any escape?

Maybe, maybe not.

Example: Seances. Story generator. Not repeated experience. No timebar. The only escape is to shutdown and never see the clip again. It’s a rekindling of the spirit of cinema. You just have to give up on interactivity.

I’ve been recording this (the seance video), so actually I’ve recaptured it within a timeline.

The timeline is a consumption paradigm (viewing time), but it’s also a production paradigm. The most interesting use of timelines in i-docs is where we are given some agency over it. i.e. The Johnny Cash Project

Adnan Hadzi

after.video: it’s a time capsule; a book in a vhs tape that gives you a cuarted view of assembled and annotated video essays.

piratecinema.org and pad.ma

Origins: Video Vortex - a collecitve in Amsterdam. Interlace.

Inspiration for computer books - Winchester’s Nightmare by Nick Montfort. You read it and you destroy the text through the act of reading it.

The In/compatible Laboratorium

The politics of referencing: We have problems accessing, remixing and referencing moving images (copyright, fair dealing, file format issues) We don’t have access to our culture anymore. We have to pirate it / steal it / seek endless permissions for it.

[Sorry - really struggled to follow along on this talk. A lot of references to things that I’m not familiar with]