Games and Empathy

People put themselves at a distance from whatever stories we hear, unless extraordinary measures are taken by the storyteller. Our inabilities to conjure the emotional and physical enormities within a news story are ingrained as a defense mechanism, and it’s one we sorely need.

Elizabeth Sampat

In the previous post, I wrote about why journalism needs to find new ways — beyond personal relevance and the utility of information — to make people care about the news. To do so, I argued, we need to encourage curiosity and empathy through the stories we tell.

But as Elizabeth Sampat noted, doing so requires “extraordinary measures” because people instinctively shield themselves from emotional transference. Reading the news with dispassion and seeking out stories that confirm, rather than challenge, our worldview are not signs of our moral failure; they’re acts of self-preservation.

How can we invite people to close the distance they put between themselves and others’ stories? I believe games are one way to do so.

Games shrink the complexity of our world, creating a safer arena to put our selves into. They give permission for us to reconnect with our sense of curiosity. They engage our imagination.

Games lend themselves to being a dialogue between the designer and the player. “Players speak to you in the breaths and pauses between the constraints you’ve created. This collaboration is precisely how something incredibly personal can become resonant and universal,” Ms Sampat says.

They can also fulfill the journalistic mission of helping people understand the world. Games may not be the best medium to record facts and events as they happen, but by making their rules visible, they teach us to critically examine the constraints and biases of real-world systems. They equip us to ask the right questions, instead of feeding us the answers.

Even Bret Victor, who argued strongly against the use of interactivity in information software design, saw games as an exception to his argument:

It must be mentioned that there is a radically alternative approach for information software—games. Playing is essentially learning through structured manipulation—exploration and practice instead of pedagogic presentation.

Bret Victor

Until recently, there have been many barriers to using games for journalism. The historical development of games have given it a “stigma of immaturity [that] is tough to overcome,” says Mr Victor.

Compared to traditional news articles, games were expensive and difficult to produce because newsrooms lacked the relevant skills and technology. It was also simply outside of the boundaries of what newsrooms thought they should be doing, given the belief that journalism consists primarily of objectively recording facts and events.

But all this is starting to change. Games sit squarely within mainstream culture and directly compete with news for people’s attention. Newsrooms have hired developers and designers, and therefore now have many of the skills needed to create digital games. Journalism’s crisis is prompting a re-examination of what newsrooms should and shouldn’t be doing and opening up possibilities for innovation.

There are people already doing this work. One example is developer Nicky Case, who has created emotionally powerful and personal games, as well as explanatory games that expose the working of systems. He has also made a tool to help others construct interactive simulations. Here’s a model of the ad-supported news industry, made using the tool.

Games as a medium for journalism is becoming more important precisely because some of the language and techniques of game design are increasingly being used in other fields under the guise of behavioural science and ‘gamification’. For example, when Uber ‘nudges’ its drivers’ behaviour through the design of its app:

When asked about the badges he earns while driving for Uber, Mr. Weber practically gushed. “I’ve got currently 12 excellent-service and nine great-conversation badges,” he said in an interview in early March. “It tells me where I’m at.”

As more of our lives are spent within such deliberately designed systems, I believe there is an increasing need for journalism that exposes system constraints and enables cultural understanding. In other words, games.

I am also interested in exploring the role that journalists can play in giving voice to others through games. Many emotionally resonant games (Depression Quest, That Dragon, Cancer, Coming Out Simulator 2014) are personal and autobiographical, but I believe they don’t have to be. One of the pillars of journalism, after all, is the journalist’s ability to truthfully and fairly tell other people’s stories.

Games have a unique power. It has so far mainly been used for entertainment. Some game designers have used it to tell personal stories. But I believe the conditions are ripe for using games to explain what is happening in the world, to author biographies instead of autobiographies, and to help close the emotional distance between people and the stories they hear.

Games changes how we see topics, it changes our perceptions about those people in topics, and it changes ourselves. We change as people through games, because we’re involved, and we’re playing, and we’re learning as we do so.

Brenda Romero

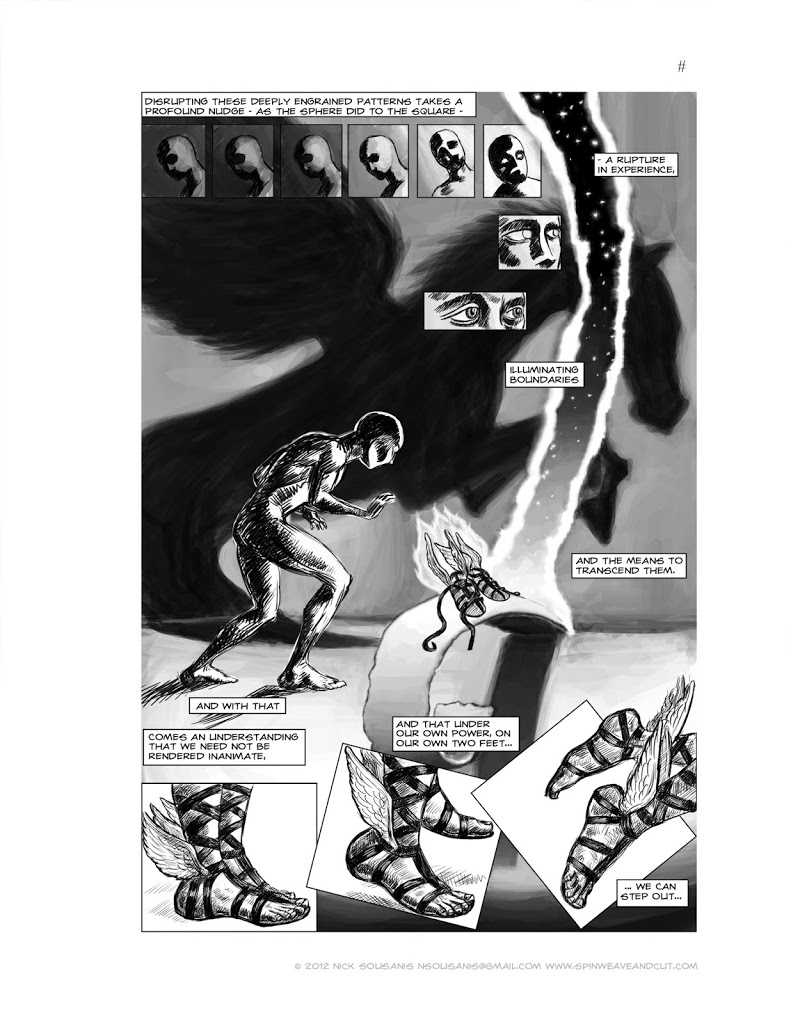

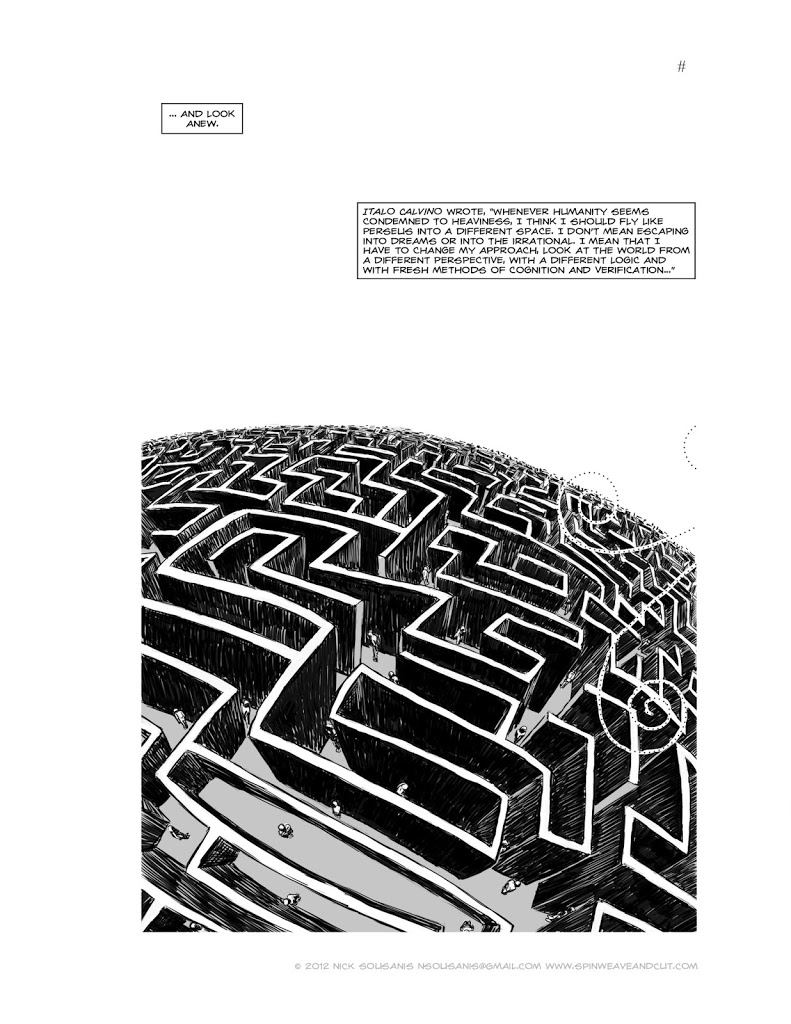

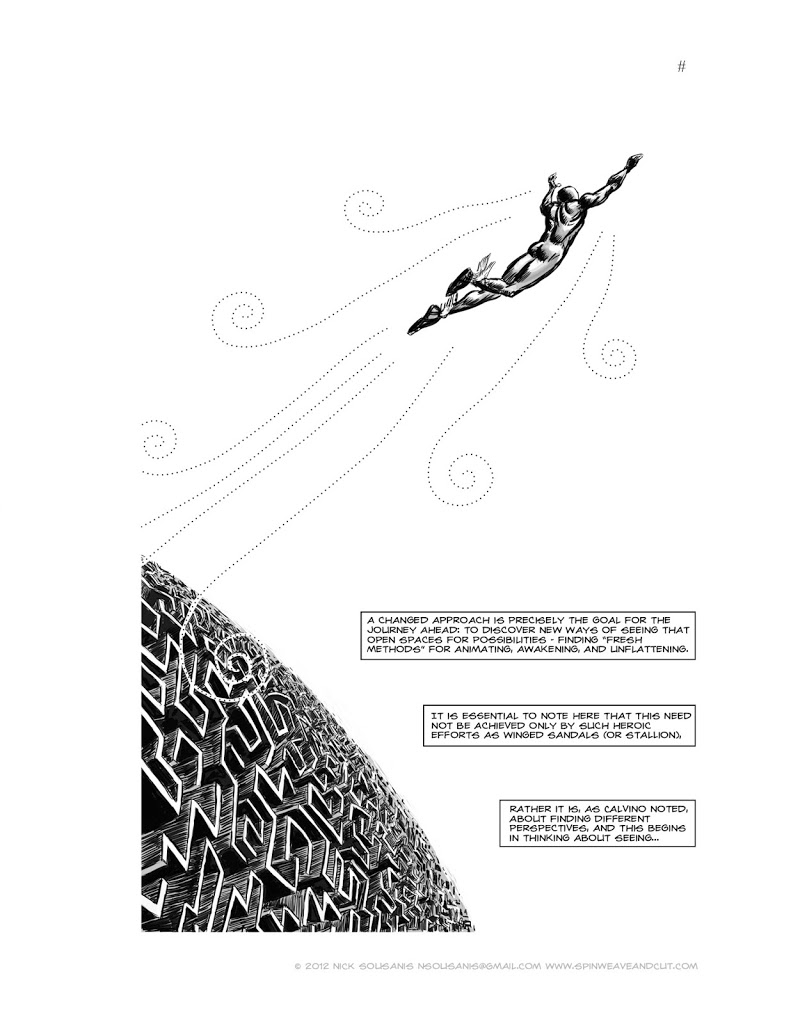

This is important if journalism is to help foster greater emotional, rather than rational, understanding. The goal is not to paralyse readers through affective empathy. But, in rupturing their shields and showing a different view of the world, to create room for growth and the possibility of creative breakthrough. As Nick Sousanis put it so elegantly in Unflattening: