Journalism that Tells Emotional Truths

Vlad Cupşa

I gave the following keynote on stage in Bucharest, Romania, on October 18 at the Power of Storytelling, an (un)conference built on the idea that well-crafted stories connect people, heal wounds, inspire, lead, and create change.

AP Photo/Vincent Thian

This is Hong Kong, my hometown and the place where I grew up.

For the last four months, I woke up every morning, eyes still groggy with sleep, and I pick up my phone and check Twitter (because that’s what I do), images like these would come flooding across my phone.

AP Photo/Vincent Yu

There has been pro-democarcy, anti-government protests happening in Hong Kong for the past four months, and the situation has escalated a lot in the last few weeks.

AP Photo

As a person, a Hong Konger, and a son of that city, I see images like these and I feel angry. I feel sad and I feel frustrated.

AP Photo

I also feel no small measure of guilt about not being there and doing more for my city as I watch all of this unfold from the safety of my home in London and the comfort of my own bed.

AP Photo/Felipe Dana

As a journalist, I see what is happening in Hong Kong and I also feel despair, but for different reasons.

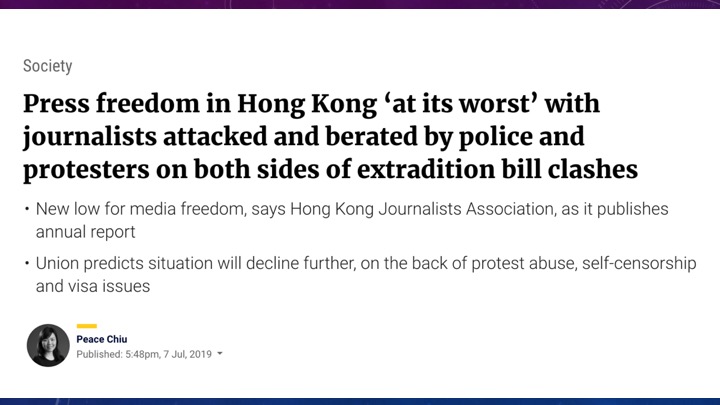

South China Morning Post

Press freedom has sharply declined since the protests started. My Financial Times colleagues, as well as other reporters and camera-men, have been tear-gassed and attacked just for doing their jobs.

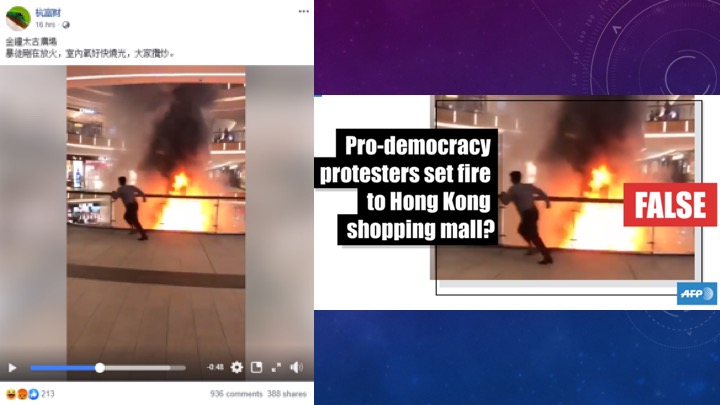

Rumours and disinformation are being created, shared and amplified on social media faster than they can be fact-checked and debunked.

And it’s being done by both sides. This one (above), about an alleged fire at one of the biggest and most popular malls in Hong Kong, was being shared by the so-called ‘blue ribbon’ - people who support the police and the government.

This one, about the supposedly horrific leg injuries suffered by a protestor when a taxi plowed into a crowd, is being shared by the ‘yellow ribbon’ - people who support the protestors.

It all contributes to a decline in people’s trust for the information they see, and their trust in the news media.

But I think there might be something deeper going on here. It’s not really that the people of Hong Kong have suddenly decided that reporters have become bad at doing their jobs of reporting, verifying and explaining the facts fairly.

AP Photo/Kin Cheung

Rather, it’s that they believe they’re in a situation so fraught, and so polarised, that it’s impossible to have an objective source of truth. It is, in a way, war. And if it is a war, then you’re either with us or against us. If you claim to be neutral and objective, then chances are that you have some ulterior motive that is suspect.

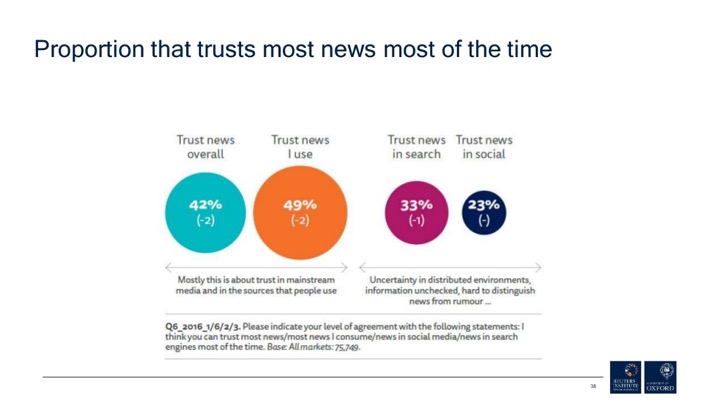

Reuters Institute Digital News Report

If any of that sounds familiar, it’s because this is not just happening in Hong Kong. The same dynamics are playing out everywhere around the world.

The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University conducts one of the most comprehensive and long-running global surveys about attitudes towards news media. In the last five years, trust in news has declined by a full 10 percentage points. This year it reached a sort of tipping point: Less than half of the people surveyed say they trust the news that they actually use. Never mind news they disagree with, or news in general.

Reuters Institute Digital News Report

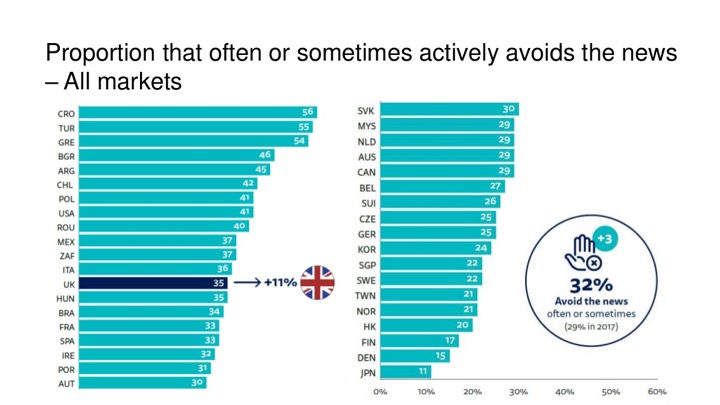

One consequence of this is people that people are tuning out the news entirely. The Reuters Institute report also found that people are increasingly actively avoiding the news. The biggest jump in this has happened In the UK, where I live, where more than a third of people sometimes or often avoid the news.

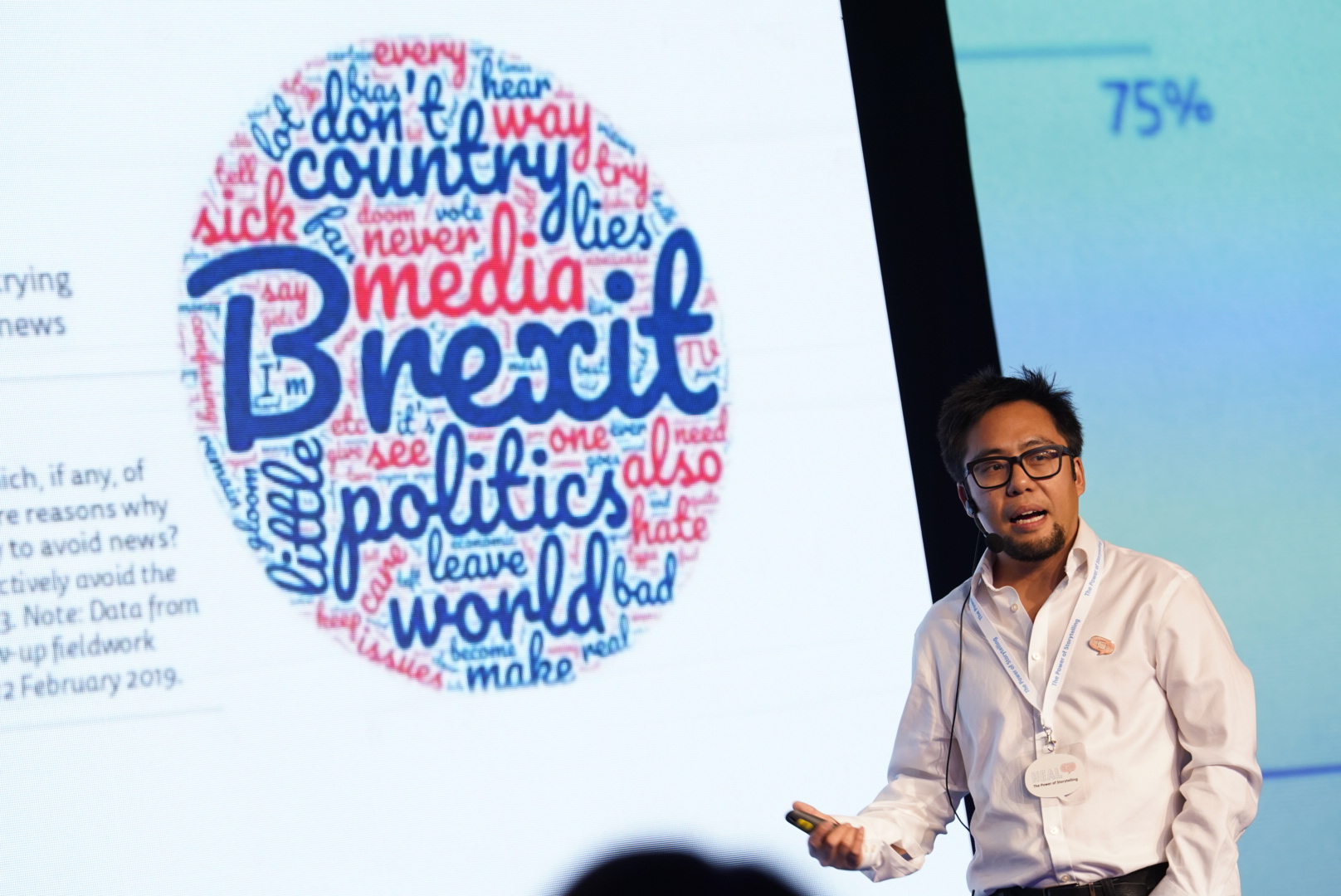

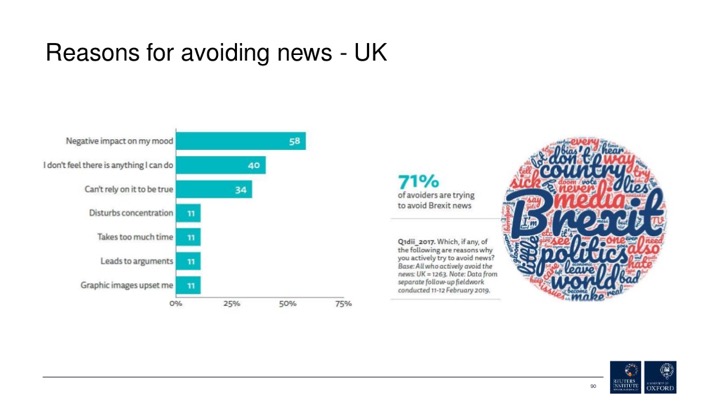

Reuters Institute Digital News Report

It’s interesting that, when we delve into the reasons people give for why they avoid the news, we find those reasons to be primarily emotional. 58 per cent say it’s because the news negatively impacts their mood. 40 per cent say it’s because it makes them feel a sense of helplessness. It’s only after that, that people say they avoid the news because they don’t trust it.

What do we, as journalists, as media, as news organisations, do in the face of this societal shift?

My belief is that we need a new kind of journalism. One that is grounded in factual truths, but also honours and speaks to people’s emotional truths. We need journalism that sparks curiosity and creates a space for exploration and understanding, instead of assuming that people will naturally be interested because what we report on is important. We need journalism that does more than provides facts-as-a-service, but also provides empathy-as-a-service.

This is the journalism that is my calling and what I’ve been doing in my work, alongside FT colleagues, over the past few years.

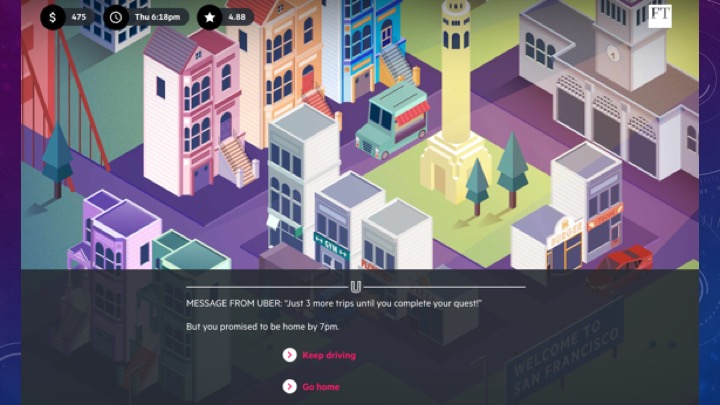

What does that look like in very practical terms? Well, it could look like news that is also a computer game.

In 2017, we created The Uber Game in an attempt to combine the emotional truths of stories with the facts of the system of the sharing economy. We wanted to put you into the shoes of someone else, and ask you to make meaningful choices as if you were that person

In this game, you play as a full-time Uber driver in San Francisco, trying to make a living in the gig economy.

You have a week to make a thousand dollars, and you do so by driving around the city and completing rides. And in the course of doing so, you come across different scenarios and dilemma.

For example, in this one (above), you had promised your son to be home by 7pm to help him with his homework. It’s getting close to that time, but you get a message from Uber that says you have just a few more rides before you complete your quest, which earns you a big cash bonus. Do you keep driving, or do you keep your promise?

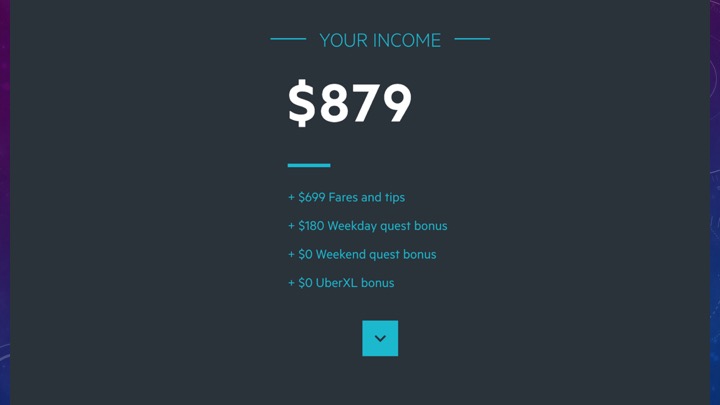

Everything in the Uber Game comes from reported facts. We interviewed dozens of Uber drivers to source not just the stories - the scenarios and dilemmas that you come across in the game - but also the numbers that underpin the system. We asked very specific questions, like, how many rides do you complete on average in an hour? or how much do you actually earn if you complete a quest?

The rigour of the reporting that went into the Uber game was really important to us because it’s what separates emotional storytelling in the service of journalism, from emotional storytelling that is being used for advocacy, activism, or advertising.

The Uber Game was a big success for us. Half a million people have played the game so far, and each have spent about 20 minutes playing the game. To put that into context, for a regular Financial Times article, the average time spent on the story is just one minute. So, twenty times improvement in engagement is pretty good. The game is also being used in classrooms, and we won a bunch of awards for it.

But beyond the plaudits and the engagement analytics, we had players tell us that it made curious, and it made them think. There were users of Uber who said it made them see their drivers as individual human beings and became curious about their lives. There were also drivers who told us that playing the game made them reflect on their place in that system.

Dodging Trump's Tariffs/Financial Times

The success of the Uber game empowered us to continue using game design techniques for journalism. Last year we made this game called ‘Dodging Trump’s Tariffs’, where you play as a trade consultant helping companies navigate the new tariffs and restrictions that have come up as a result of the US-China trade war.

Again, everything in the game was based on factual reporting - in this case data from the Commerce Department, as well as filings from actual companies asking for exemptions from the tariffs.

But we also wanted to get an emotional truth across: that Kafka-esque feeling of being trapped in an uncertain and capricious bureaucracy where the rules are unclear and changing.

I’ll mention this one quickly only because we launched it just before I got on the plane to come to Bucharest - our third newsgame was released last Friday, and it’s about trying to balance profit and purpose as a chief executive…because CEOs need empathy too?

I grew up playing computer games and they will always have a special place in my heart. They bring stories and systems together, and are a powerful format for our times because our lives are increasingly governed by algorithms and systems.

But I think they’re just one example of how we can harness the power of emotional storytelling in journalism.

What if we brought journalism and poetry together?

This was a documentary film about the Irish Backstop.

And just a bit of explanation and background very briefly: The Irish backstop has been one of the most contentious issues about Britain’s exit from the EU. It’s essentially an insurance policy that sets out what is going to happen on the Irish border, with customs checks and immigration checks and so on, if the UK and EU fail to agree a Brexit deal.

Of course, the Irish border is a real place, with a real history of conflict, and real people living on both sides of it. My colleague Juliet Riddell, who masterminded this film, really wanted to get that perspective across. So she commissioned Clare Dwyer Hogg, an Irish poet, to write an original poem about Brexit and the Irish backstop, based off of articles that we have written in the FT. We asked the Irish actor Stephen Rea to perform a reading of it on location at the actual border, which Juliet turned into this beautiful film.

This film was also a big success for us, with showings at film festivals and people saying it gave them a different perspective of the backstop issue. But again, poetry is just one format that lends itself to conveying emotional truths. What if we combined journalism and theatre?

This is another film made by my colleague Juliet. For this one, we worked with a writer from Royal Court theatre, as well as climate scientists, to explore what the news might be like in 2050 if we don’t act now on the climate crisis.

Both of these films were released under the brand of FT Standpoint, and we see them as the visual equivalent of our opinion pieces in the newspaper - they’re based in factual reporting, but they definitely also have a point of view and an opinion element in them.

But still it was really important for us to get the factual underpinnings right. The reason why you heard Manchester and Austin mentioned for that bit about the temperature reaching 50 degrees, was because that’s what the climate scientists have projected, based on mathematical models and facts of what we know is happening now.

And I think it is precisely on topics such as climate change and Brexit that emotional storytelling can have a big impact. These are widely reported topics, where the facts are abundant and evident. But they’re also topics on which people have already formed strong opinions on, and are probably fatigued from hearing about the facts. Emotional storytelling lets us break through that and help people look at these issues with fresh eyes and a fresh perspective.

That, I think, is the power of emotional storytelling. Emotions can affect cognition. It can help people open their world up and be curious about new facts, or it can close their world in.

And it’s precisely because emotional storytelling is powerful, that I think it is important that journalists grapple with the complexities of using emotional storytelling - even though we won’t always get it right, and we open ourselves up to accusations of bias when we get it wrong.

It’s important because intentions matter. We’re by no means the only ones alive to the power to emotional storytelling.

Advertisers use it to get your money.

Politicians use it to get your votes.

At least when journalists use it, it’ll be in the service of telling the truth.

Fortunately, my colleagues and I at the Financial Times are by no means the only ones experimenting and doing this sort of journalism. There is a growing movement of people using emotional storytelling in journalism, and it’s happening all over the world.

This was South Africa, where last year the Open Societies Foundation funded a project to bring together investigative journalists and local theatre makers and artists to create new pieces of theatre and artwork based on the journalists’ investigations. It was great not just because it brought journalism to new communities, but theatre too. The works were performed in local dialects for people who would not normally buy a newspaper or a ticket to go into a theatre hall.

The performance you see here (above) is based on the Life Esidimeni scandal, where more than a hundred mentally ill patients died when the government transferred them from a fairly well run public facility to ill-equipped NGOs and private facilities with next to no oversight. The play use the concept of a chorus in Greek tragedies to give voice to the grief of the families of the victims, and the cool thing about this was that the entire set of the play fits into this metal trunk, which lets them take the play on tour to be performed in community centres, villages, schools, etc across the country.

This is the De Balie culture centre in Amsterdam, where they have pioneered a form of live journalism, that combines traditional reporting with theatre and policy discussions to ask the question of what it means to bring an investigation and reporting into a topic into a space over a period of several months.

They are using theatre and performance to not just convey an emotional understanding, but also to create a space for dialogue between people on different sides of an issue. In this project, the reported facts about the ‘working poor’ in Amsterdam, and the emotional storytelling in the portraits of the working poor, provide a jumping-off point to have substantive civic conversations that lead to healing and to real-world policy impact.

And in the UK, The Bureau Local have been hosting similar Story Circles - events where they invite people directly affected by the issue they are investigating to come and share their stories.

This is one they did recently in Edinburgh was about homelessness and the barriers to housing.

So this is good. There’s momentum behind this kind of journalism; more people are experimenting and doing projects and exploring how we can combine emotional storytelling with factual reporting in novel ways.

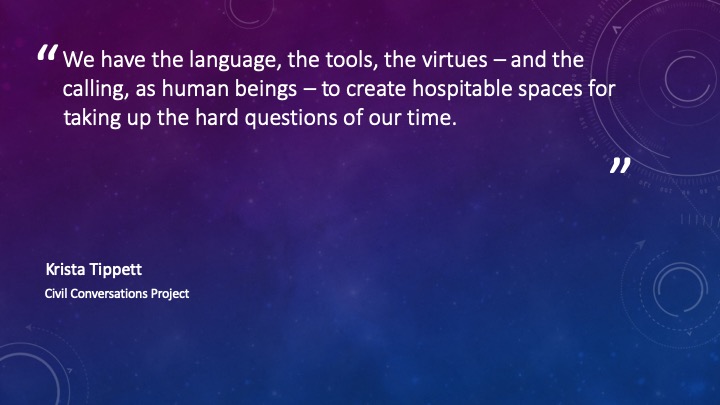

But I do sometimes wonder if that’s enough. To paraphrase Krista Tippett, we as journalists do have the tools and the virtues to help society take up the hard questions of our time. We can use emotional storytelling to draw people in and open them up to the world; we can use facts to ground the conversation in reality. But the actual work? The actual grappling of the hard questions? That needs you. It needs all of us to put the work in.

AP Photo/Vincent Yu

You can’t force healing. The conditions and the timing has to be right. As for Hong Kong, I don’t know if now is the right time for healing. I suspect it’s not yet, because the wounds are still being carved as we speak. But I hope that one day, that time will come and when it does, I hope that journalists will be there to help play a role in the healing process.

Thank you.

Bucharest, October 2019