Lessons from making the 'Dodging Trump's Tariffs' newsgame

In Dodging Trump’s Tariffs, you play as a Hong Kong-based trade consultant advising chief executives via a series of emails. They run a variety of companies, all looking to import goods into the US that are caught up in the US-China trade war. The CEOs would like your help to minimise the tariffs’ impact…even if it sometimes means circumventing the law.

This is the second newsgame I’ve worked on at the Financial Times. Although there are a lot of surface similarities between this and The Uber Game (both are about the player making choices that affected the narrative), we actually took quite a different approach.

Is it a news story, or a news game?

With The Uber Game, we deliberately tried to stretch the definition of a newsgame in the direction of a game-like experience. The reporting that underpins everything you experience in the game is not immediately obvious to the player. You could play it entirely as a game, without really being aware of how it ties into the news.

With Dodging Trump’s Tariffs, we leaned in the other direction. The link between game-like elements and the underlying reporting is made explicit and clear. There is no option, for example, to skip over the ‘data behind the story’ sections.

Also, while your choices generate positive and negative feedback, there isn’t a single score to maximise. Winning is getting through all the emails and learning something about the broader situation of tariffs, rather than figuring out the specific responses that would make every CEO in the game happy.

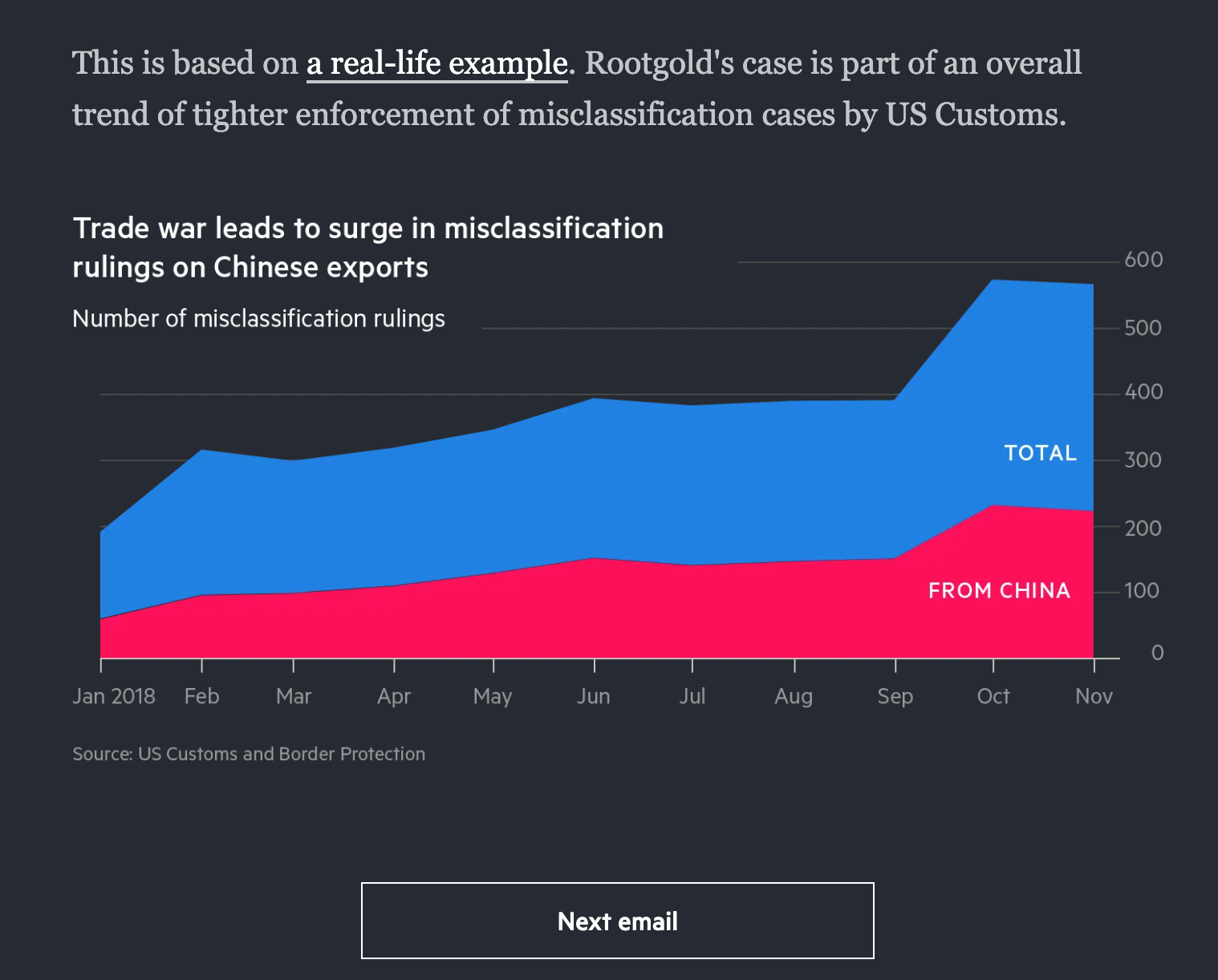

A 'Data behind the story' screen in Dodging Trump's Tariffs

Complete and incomplete information

Dodging Trump’s Tariffs is in many ways closer to a piece of interactive non-fiction than a game.

This design decision is partly driven by constraints. With The Uber Game, we gathered enough information to construct an economic model of a full-time driver’s business, which allowed us create a simulation and to make fact-based decisions on win and fail states (for example, whether you drove enough to earn the ‘quest’ bonus or not).

With Dodging Trumps’ Tariffs, however, we had incomplete information. For example, we had access to the database of US Customs rulings, which told us that there had been a surge in companies being caught misclassifying printer parts. We did not know, however, whether this meant that the player would likely succeed or fail in the game if s/he attempted to do so — companies that were not caught would, by definition, not be in the database.

Interviewing trade experts and other reporting helped round out some situations, but it was impossible to have enough information to construct an accurate and detailed model of US-China trade in such a volatile situation.

The printer scenario in Dodging Trump's Tariffs

This pushed us to approach the design of the game in a different way. Instead of writing a narrative that carried the player through the course of the game, we saw each email as a vignette. Play through enough of these vignettes, and you would hopefully get a sense of the whole system. An early version of the game even randomised the order of the emails.

Frustration and helplessness

Dodging Trump’s Tariffs explored a major challenge for newsgames: How do we design an engaging experience that conveys frustration and helplessness?

Newsgames, or ‘serious games’ in general, cannot just be about entertainment and feeding power fantasies. They are meant to help people understand systems, or to convey a message rooted in facts. It’s unavoidable that, sometimes, that message is the feeling of individual helplessness in the face of larger and more complex systemic forces.

While there were elements of difficulty and frustration in The Uber Game, it ultimately still preserved space for individual agency. In Dodging Trump’s Tariffs, we tried to take even that away: you are merely a consultant providing advice, and in general the results of your choices are deliberately unpredictable. It is almost inevitable that a first time player will end up with at least one unhappy client.

An unhappy client in Dodging Trump's Tariffs

The risk of trying to convey frustration is that you end up with and try to justify poor game design. When players feel frustrated, how do we orient their frustration towards the system, rather than the game that is trying to depict the system? I think the constant reminder of the ‘data behind the story’ helps to do so.

I think designers trying to convey frustration also needs to help players know that it’s ok to feel frustrated. This is where I think we could have done better, either through the wording used to frame the negative outcomes, or by allowing players to ‘skip to the end’ and learn about the story through passive reading rather than active participation.

Iterating

Dodging Trump’s Tariffs was made with entirely different colleagues than The Uber Game, but we still built on and benefited from the earlier experience. I didn’t have to try to learn Ink (the narrative scripting language we used) from scratch, and we were able to refer to the guide that our colleague Ændrew wrote, on how to render Ink’s output onto a web page.

Some things remained difficult: fitting everything onto small phone screen sizes, for example, and fixing the position of the buttons so they don’t move depending on the length of the text, but in general we were able to move much quicker, and cut production time to around three weeks, as a result.

What to read next: Games and Empathy