Three conversations: UX, transitions, and theatre

I’ve had the good fortune to talk to interesting people about digital storytelling and the use of interactivity during my Nikkei-FT Fellowship.

Here are three particulary interesting conversations.

A UX framework for evaluating interactive experiences

This comes from Celia Hodent, who is bringing user experience design and cognitive psychology to game design. Pre-order her book! Watch her Game Design Conference talks: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

Good interactive experiences combine both usability and engage-ability.

Usability

Usability is about making it easy for people to use a product, system, or service, so they can accomplish their goals. Primarily, it is about reducing friction points by accounting for human perception, attention, and memory:

-

What do they perceive? Can you apply the Gestalt laws of perception to make the user interface more easily readable? What affordances are being signified by the cues you provide? Are you helping them create the right mental model of how it works? If they make a mistake, are there correct and sufficient feedback for them to adjust their mental model?

-

How much are you asking them to remember? Do you really need them to rely on their memory, or can you provide reminders?

-

Human attention works like a spotlight: are you directing that spotlight to prioritise learning? Or are you dividing their attention?

Most critiques and evaluation of interactive news and data visualisation centres around usability. The most prominent example of this being: “Does it work on mobile?”

This is important, but in Celia’s framework, there is a second, equally important aspect to good user experience desgin: Engage-ability.

Usability explains how a person will use the thing you designed; Engage-ability address why they would use it, and stick with it.

Engageability

Celia breaks engage-ability down into three buckets: Motivation, Emotion and Flow. (She gives a detailed explanation here)

Motivation

Why do humans do things? Who knows. There are loads of different theories, but a prevailing framework is Self Determination Theory, which identifies three human needs driving intrinsic motivation (i.e. motivation for doing an activity for its own sake):

- Competence: A big reason why low use-ability turns people off, since it challenges their sense of competence.

- Autonomy: The need to have volition and make meaningful choices. This is one reason why even if a static visualisation is more usable, people will still try to click on it and expect things to happen.

- Relatedness: People need to have meaningful relationship with others. Note that this can be manifested either through cooperation or competition.

Intrinsic motivation can be deterred, or reinforced, by external sources of motivation (rewards and punishments). This is why motivation is so hard to study and design for.

Emotion

Emotions are powerful drivers of behaviour, and are influenced by how we judge a situation against our expectations. This is influenced by design, but is probably one of the least analysed and discussed aspects of interactive news and data visualisations.

Flow

The space between anxiety and boredom. There’s plenty of literature on this. It is also less relevant to most existing pieces of interactive news / data visualisations, which tend to be short snapshots that conveys one main point. It might be more useful, however, to consider the use of flow in the context of how a person engages with an entire news site.

Transitioning between different media formats

This came from a conversation with Nick Sousanis, who is teaching how comics can encourage a different way of seeing. Buy “Unflattening” - originally his PhD thesis!

Snow Fall hinted at the possibility of the web enabling the combination of different media formats to create compelling immersive experiences. But in the five years since it was first published, that vision has mostly turned out to be a mirage, becuase, guess what? Transitions between media types are hard to get right.

As Brian Boyer wrote in a 2016 NICAR email discussion:

My current grand unifying theory of good digital storytelling can be summed up as such: Don’t make the user switch modes.

The longer version: You’ll frequently see stories with a text component, a slideshow, a handful of videos, etc. Getting somebody to switch from reading, to watching, to listening, is too much to ask … You either have to never switch modes, or ease the transition from mode-to-mode.

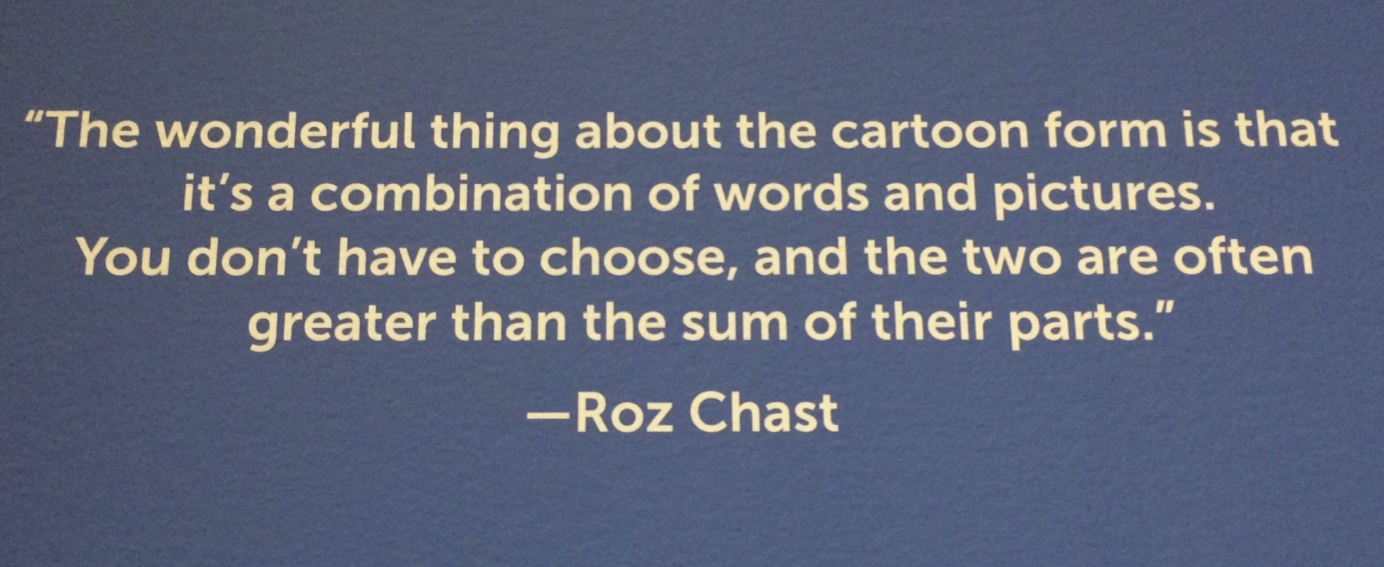

And yet, not all transitions are equal. Comics asks its readers to constantly switch between processing words and pictures. How is it that this is seen as a strength of the medium, when bringing together different media types in Snow Fall-like pieces is seen as a weakness?

Part of the answer is that not all transitions are equal, because different media formats have different properties. Nick suggested that you could separate formats into two categories: time-based media like video and audio, where the content changes over time, and static media, where content stays the same over time.

Transitioning across categories is much harder than transitioning within categories. “The static nature of comics is what makes them powerful,” Nick says. “Comics lets you spatialise your thoughts.”

If we are to create multimedia stories, there is much we can draw from comics’ extensive vocabulary and techniques in combining words and images. (Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics is, of course, the canonical starting point).

More broadly, I think comics points the way towards a different kind of interactive and digital storytelling: one that escapes the linearity of traditional narratives. This type of ‘Ideas Comic’ is exactly what Nick is working on, as he tries to answer the question:

“How do I get an idea across [to the reader] in the shape of a page, in a way that’s very diferent from a story?”

Brechtian Theatre

I’ve been exchanging email correspondences with André Piza, a producer and theatre director who works with People’s Palace Projects. We’ve been speaking about the challenges in reframing journalism as a collaborative effort between readers/audience and journalists/artists.

“There is a strong parallel here with how the arts try to respond to the demands of their own audience, regardless of whether you are a West End producer or a publicly-funded community theatre,” Andre writes in response to my previous post about creating a need for news.

“There are theatres pushing the boundaries of established practice but, generally, they still believe that audiences want to see what they can easily understand, categorise and fit into a recognisable box. Anything else is either unaccessible or confrontational.”

We agreed that one way to move beyond this limiting view is to rethink the role of the story:

“The story is crucial, but it serves a purpose - it is not the main objective. The objective is a rather engaging kind of meeting, encounter, conversation.”

This requires taking audiences outside of their comfort zone, a theme that has been explored in thetare by Bertold Brecht, who proposed “a kind of theatre that didn’t disguised the ‘artificiality’ of the theatrical event”.

“One of the things he played with was allowing people to smoke and keeping the lights on during during the performance (Brecht was a cabaret writer/director before anything else). At any dramatic peak in the show, characters would snap out of the action and do something unexpected (to the naturalistic theatre audience) creating this “estrangement” effect (“defamiliarization”) which would put the audience on an inevitable position to reflect and try to make sense of, make a decision or create an opinion about what was happening.”

We are starting to see some of this in how the data visualisation world grapples with conveying uncertainty by adopting forms, like sketching, that “feel like a looser medium”. But I feel we’ve merely scratched the surface of what we could do by breaking the fourth wall, or deliberately creating surprise or tension.

I’ll end with a a hopeful note from André:

If science, the media (or part of it) and artists could convey the message that it is alright not to have definitive answers and we can still move forward, have fulfilling lives and navigate all that while searching for the best questions, driving our curiosity, I think we will live in a better world.

What to read next: Lessons from the Exploratorium