Epic 2018 day 1 conference notes

Excited to be back!!

Conference Chairs’ Welcome

Theme of this conference: What counts as evidence?

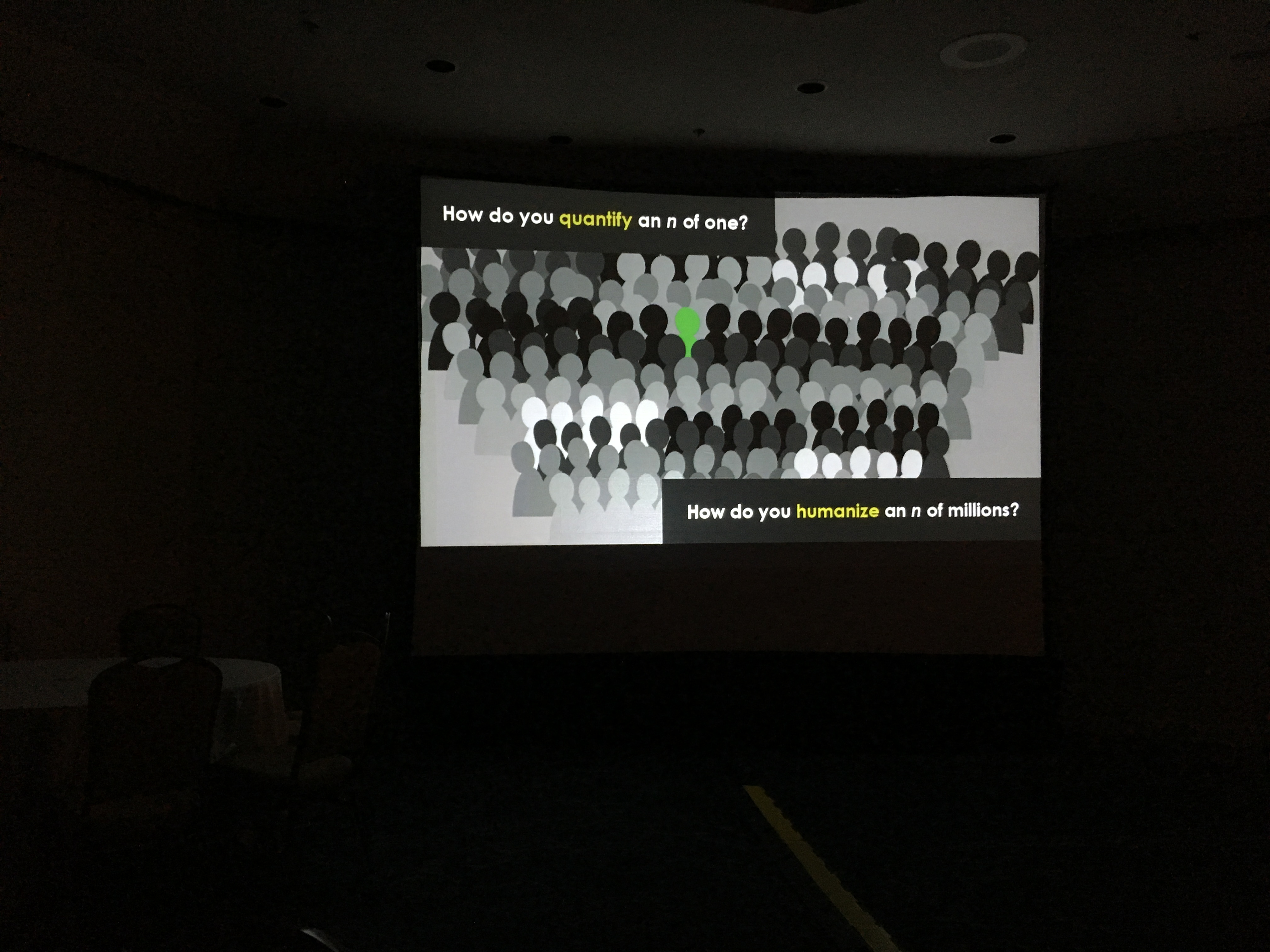

[missed a chunk here, but basically - a large part of this conference is an experiment in bringing quant and qual together]

This is not just a response to some technical development (i.e. big data, AI etc)

But there are things happening in the world that make this particularly relevant: For example:

-

the post-fact, fake news world

-

Rise of Audit Cultures: Org’s obsessions with metrics become self-fulfilling prophecies without regards to consequences. leads to bullshit jobs (Graeber)

“Ethnography doesn’t give you a get-out-of-bullshit-free card”, but gives us a chance to find some meaningfulness in a sea of bullshit

“Bullshit actually has a really specific definition in philosophy”

The problem of indifference has now taken on an entirely new salience.

The workers in this hotel are contemplating a strike. others have done so. in part this is about their evidence and their needs have not been heard. They’re striking over the ability to meet basic needs, to be protected against sexual assault, and the ability ot be involved in decisions about automation that affect them.

The problem we have with evidence is not an audit culture problem but a Hannah Arendt problem. We can make better or worse choices about what we measure and how measure them, but we can also make decisions about how to keep measurement in its place. When power coheres with indifference, when evidence starts to not matter, then we should worry. Because no one escapes unscathed from that.

Arendt: Evil happens when people get exceedingly good at doing their job only within narrow confines, when people get really good at bullshit jobs.

Re: hotel workers - the difference is not between truth and untruth, but truth and uncaringness.

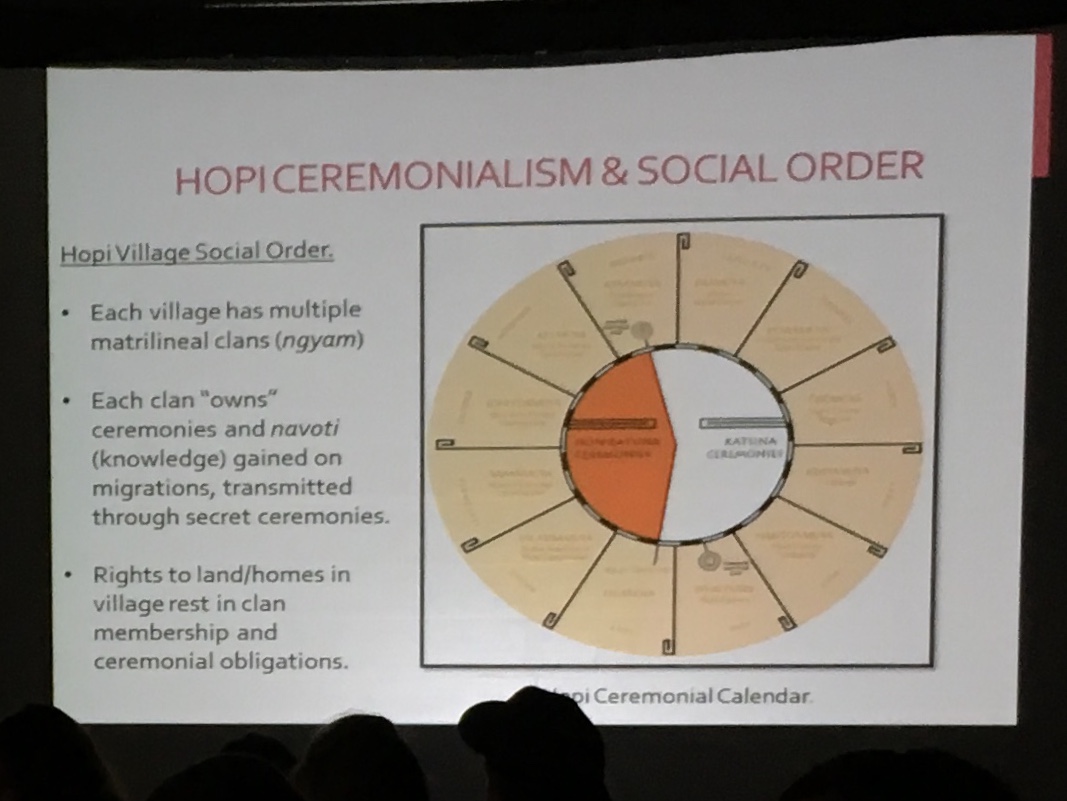

Keynote: Cooperation without submission: Some insights from Hopi-US Engagements

Justin B. Richland is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Chicago and Research Professor at the American Bar Foundation. His research explores the language, culture and politics of contemporary Native American jurisprudence.

Shows an illustration of Ethnologist Mathilda Coxe Stevenson trying to enter a hopi kiva.

At the time, this was a photo of intreprid researcher/ethnolographer. Nowadays its an image of Hopi refusal.

This talk:

What do Hopi-Euro/American interactions tell us about how knowledge is produced and communicated between two groups that don’t have much in common.

The limits that the Hopi present to Euro-American knowledge resonates with how they police knowledge within their culture as well

Their refusal to share knowledge doesn’t shut down relations, they are invitations to participate on Hopi norms and values.

How all this study led to a scene of Hopi ‘meaningful tribal consultation’

The way Hopi engages is more than just about conveying information, its enacts the relationships, values and norm that allow the transfer of knowledge at all.

Knowing, norming and relating

Classic definition of knowledge: “justified true belief”

i.e. S knows proposition P iff: P is true, S believes P is true, and S is justified in believing that P is true

Key bit he wants to focus on here is ‘justified’. Why is this necessary?

Robert Brandom: coin-toss thought experiment.

Say I tell you before I flip it that I believe it to be heads. aaaannnd…

(flips coin)

it turns out to be head.

So, was it a true belief? (yes)

But did he know it was going to be heads?

Probably no (because doesn’t fit ‘justified’ criteria)

We’d want to know more behind the resoning. but what reasons would count? The bar for what counts as ‘justified’ is a shared norm.

This is the same as for the Hopi, when it comes to their secrets and knowledge,

Hopi knowledge & consultation with USFS

What Hopi are taught in their culture: cooperation without submission

Hopi reservation in Arizona - about 70k residents, 12 villages around 3 mesas. Before 1936 they (each village) were self-governing. In 1936 they were federated into a Hopi tribal nation.

Each clan contributes to the making and remaking of village community is by performing ceremonies.

Navoti: Secret ceremonial knowledge of each clan, a source of decentralised social power and authority.

This poses a problem for Anglophones who want to know everything For Hopi, the certainty associated with not-knowing is a form of cultural knowledge

The consultation: wanted to know about a piece of Tonto land and proposal for private sale. Turns out the land doesn’t just contain sites of human habitation, but is bound with their obligations to care for the land. It’s not just a space, it’s a place

Hopi objected to the information that the USFS planned to sell the land, and that the forest archaeologist suggested excavating the sites (and wanted Hopi co-operation to justify that so that they could apply for federal funds to do so). But they agreed to continue the consultation.

The official criteria and rules for what counts as ‘significance’ underwrites a scientific understanding and ignores the Hopi way of life and their understanding of ‘significance’

An intervention happens during the expedition: A grey hawk lands nearby. Hopi interpret it as the visitation of an ancestor.

This obligates them to take offerings down to where the grey hawk landed and leave it there.

Conclusion

The Forest Service didn’t end up listening to the Hopi, and sale of the land was completed by the end of Summer. Some of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office expressed doubt as to what the point of the consultation was at all. But:

“Heck, if Cortez came to consult, would the Hopi do it?”

“Yes: I guess even the ignorant have to be treated with respect”

We have to agree on the norms and values of what is and isn’t evidence that will justify our true beliefs.

Even in this time of alternative facts and fake news, these question seems more pressing than ever. They beg more questions - around epistemology and whether its wide enough.

Maybe what we can all do for each other right now is to engage in a bit of cooperation without submission

Q: Is the evidence of embodied stories of ancestors or other similar kinds of evidence ever as convincing for action as “science” (forest service in this case)?

A: depends on what you mean by action, and what science produces. The question of what is true echoes what we care about. This echoes Bruno Latour and climate change sceptics and how they take up social embodiment of knowledge. We should not be talking about matters of fact at all but matters of concern. What are the ends to which the facts and knowledge are being used?

Q: Can you talk about your selection of quotes from Hopi team members—and transcription conventions on your slides—as practices of evidence making?

A: I’m very much a part of the knowledge production around Hopi and held at arms length by them (despite working with them for 25 years and an appellate judge on their court). they vet the transcriptions. You are constantly making choices about what to include and wht not. every transcript is a theory of what counts. have different sets of this transcript - some that shows syllabic breakdown, some that shows inbreath and outbreath, etc. each of those is to make a case. These were chosen to show where assertions about traditional knowledge were being made. Again, it depends on what your concern is.

Our profession needs to do a better job at translating the labour intensivity of our work.

My key takeaways:

- We should speak about matters of concern, rather than matters of fact

- Knowledge cannot be separated from the shared norm and values that separate what is justified and unjustified belief

- Maybe what we can all do for each other right now is to engage in a bit of cooperation without submission

- Every transcript/artefact of knowledge production is a theory of what counts

Rehumanising Data

Mattresses & Moneyboxes: Cultural Affordances for Microfinance in Jordan

Zach Hyman · Continuum (@sqInchAnthro)

The challenge: Design a service that allows clients to more easily receive and repay loans.

Set off across Jordan - 5 different cities and villages, using stimuli - illustrated cards - to talk about anything that we thought might affect their ability to repay microloans.

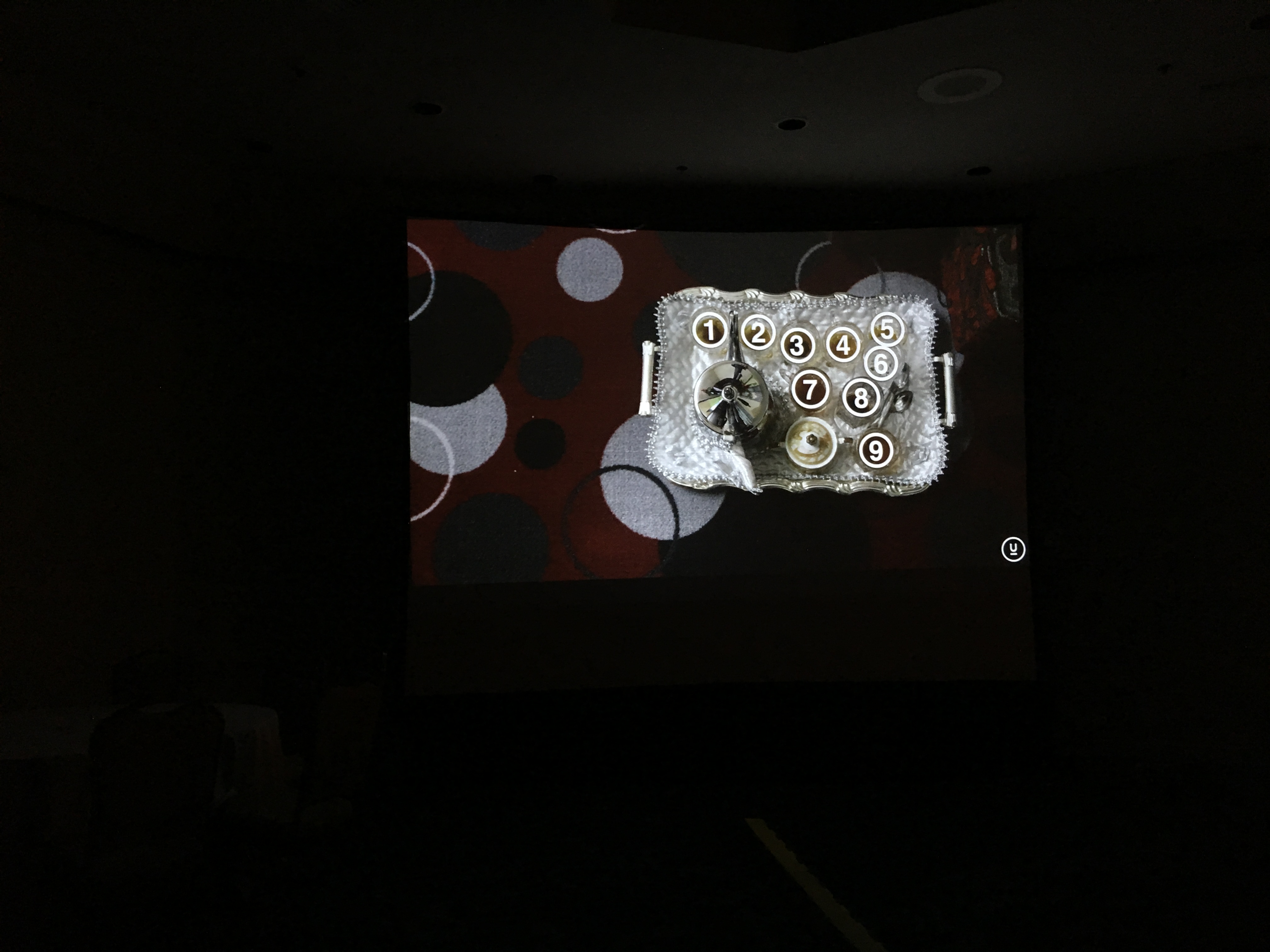

Very quickly in one of the conversation a woman came with a tray of teas - one for each person there, and they then sat down and participated in the conversation as a social event, even though she had no knowledge of microloans.

Why did she interpret it as a social event rather than a formal interview? Our local fixer advised providing in-kind incentives instead of money, so we brought boxes of stuff, and to make it less intimidating we put bows around it - it looks like a gift.

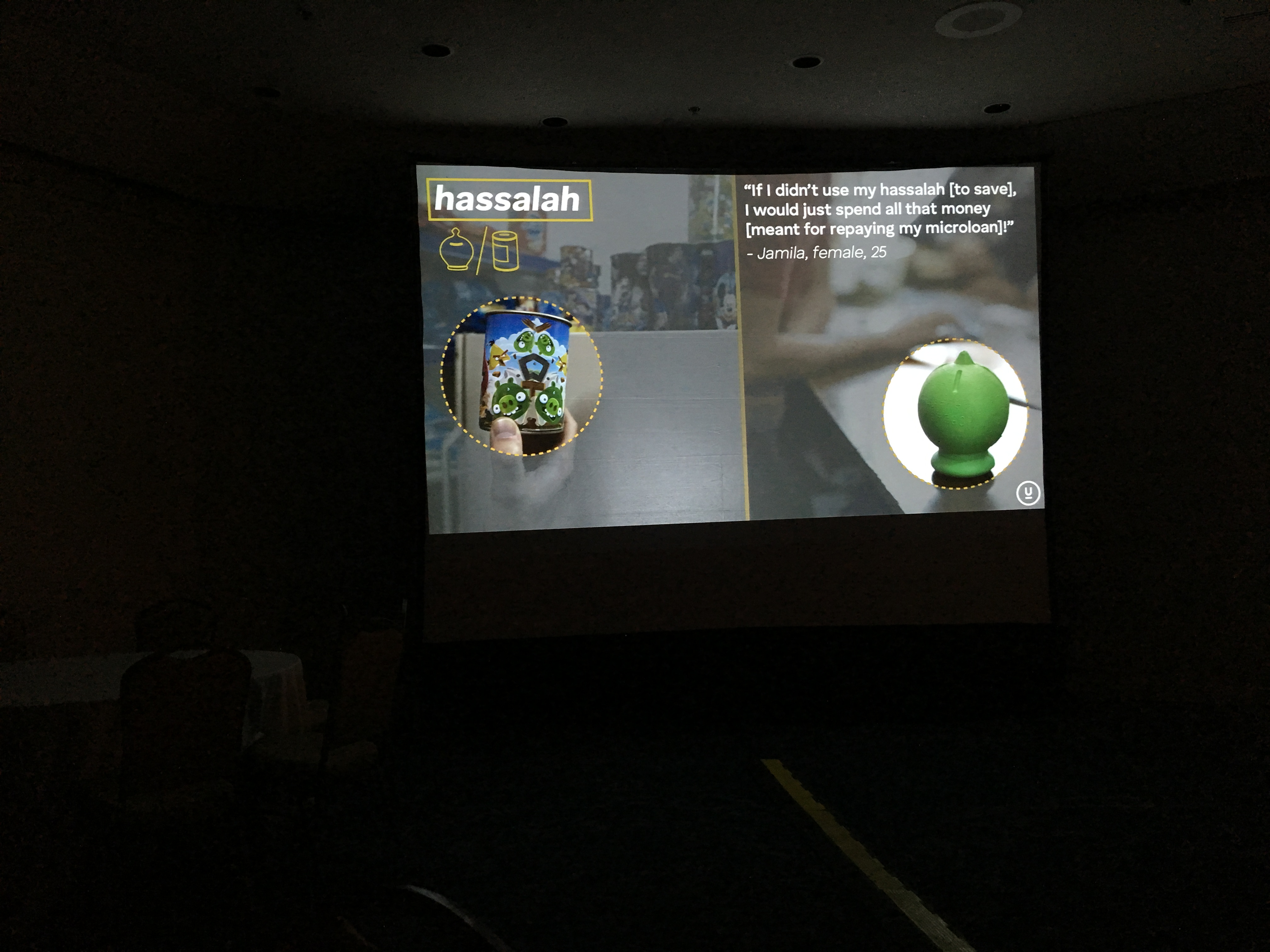

Some things they found: Remoteness of villages from bank branches. The difficulties in saving that comes from unexpected happenigns, and objects such as hassalah - what westerners might call piggy banks.

We found that those who most often repaid microloans were people who used hassalah

Cultural affordance: a culturally specific, iconographic image. for example - the iOS notepad is yellow lined paper, but in Japanese culture, notepaper is white background, dotted grid.

We saw that people in Jordan used wallets to store money. But that they do NOT use their phones for storing money.

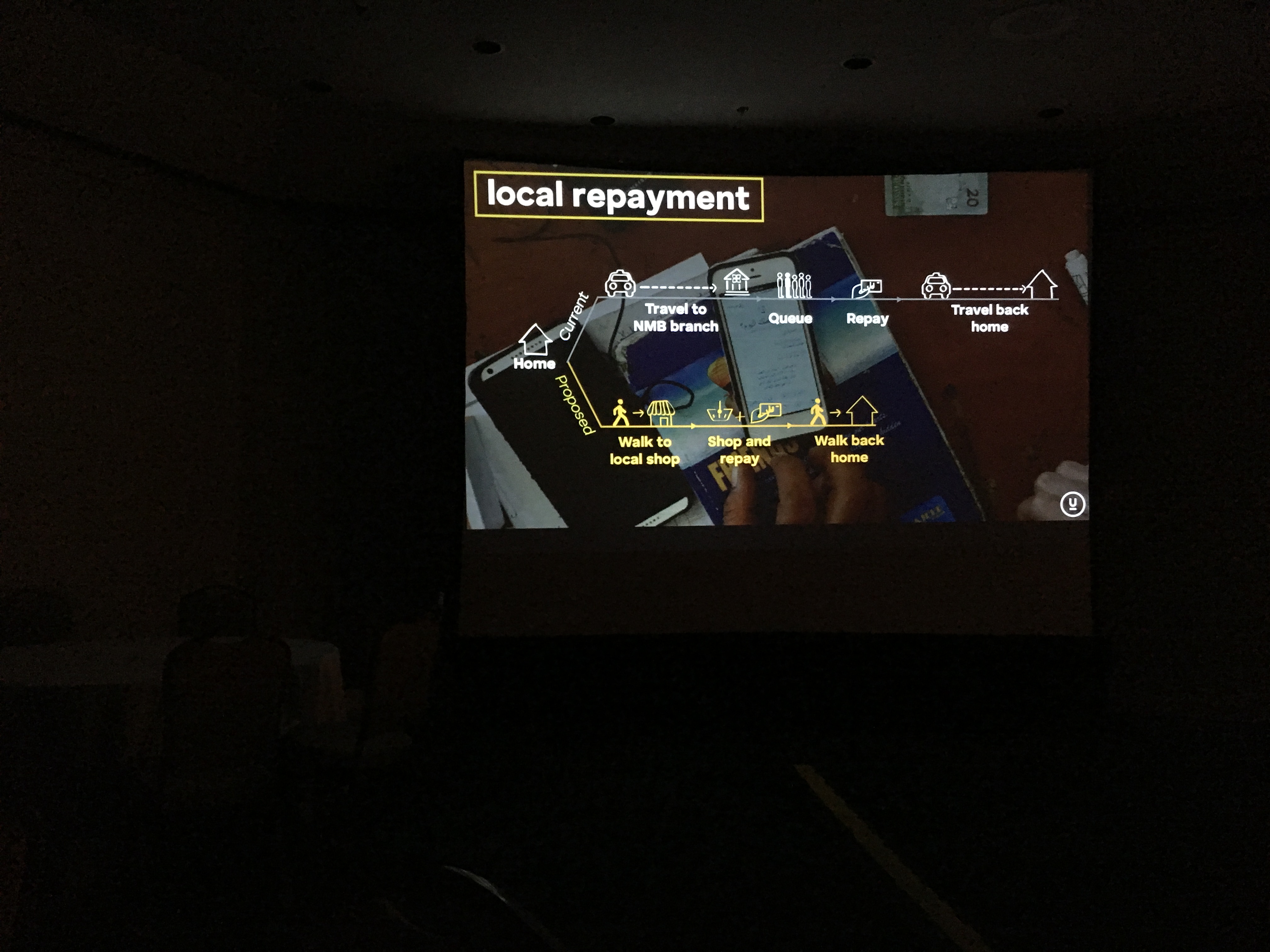

So we tested something based off of the hassalah. Something that helps people save a bit of money regularly. We made phone as an anciliary device and the centre of the product around in-person interactions with trusted local merchants.

Not all of our recommendations were immediately adopted, but it’s clear that our ethnographic research created clear wins.

They could make gradual repayments at local phone shops, could submit documents via taking a photo on their phone, give clearer receipts and loan tracking (addresses worries around losing paper receipts)

Q: What makes a reallly good fixer? A: Someone who can roll with the punches. Try to find fixers who have worked with journalists before.

When Customer Insights Meet Business Constraints: Building a Go-to-Market Strategy for a Smart Home Offering in a Regulated Space

Liz Kelley & Amanda Dwelley · ILLUME Advising

Every project operates under constraints - but this had some special constraints: State regulation needs them to prove that the product would result in energy saving for consumers. Also, when we were brought on, customer had already chosen a product and a vendor.

So, there were already assumptions and constraints in place. But, what if customer needs don’t align with client assumptions or project constraints?

With large-scale research projects, you only get the answers to the questions you ask, so it’s important to put the ethnographic / qualitat

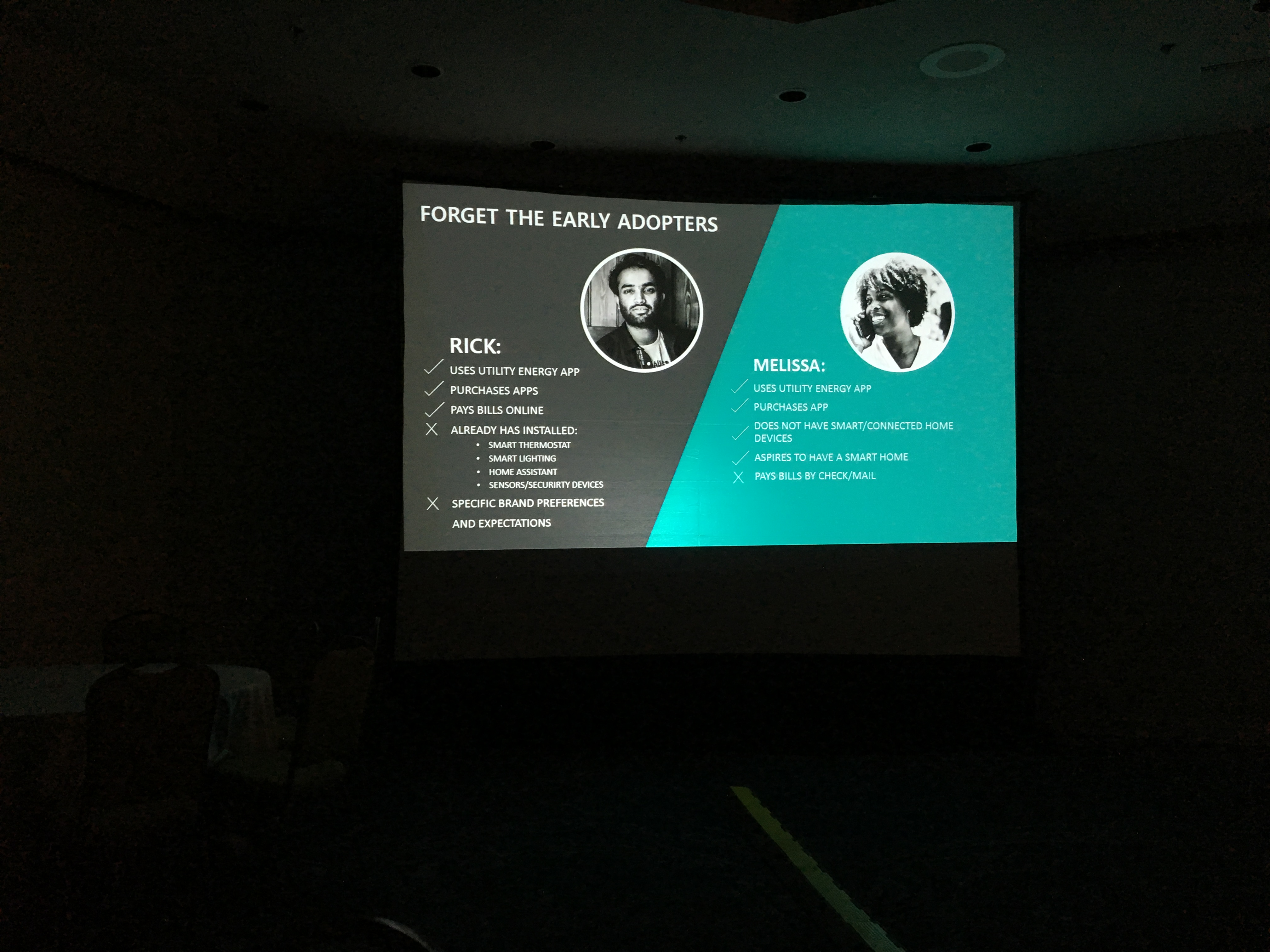

Client assumed that product would appeal to early adopters, like Rick. But when we went in and did research, found that they were actually already using other/rival services and are sceptical about using an offering from a utility. Instead, found people like Melissa.

This allowed them to surface the areas in which the product features don’t match up with customer and utility preferences.

Other things we learned: Security is often framed around being secure against an outsider or force, but actually customers saw it as security and safety of the family members within the home

This helped:

-

refine concept

-

more realistic estiamte of the size of the market and rate of adoption

-

better propensity scores for individuals:

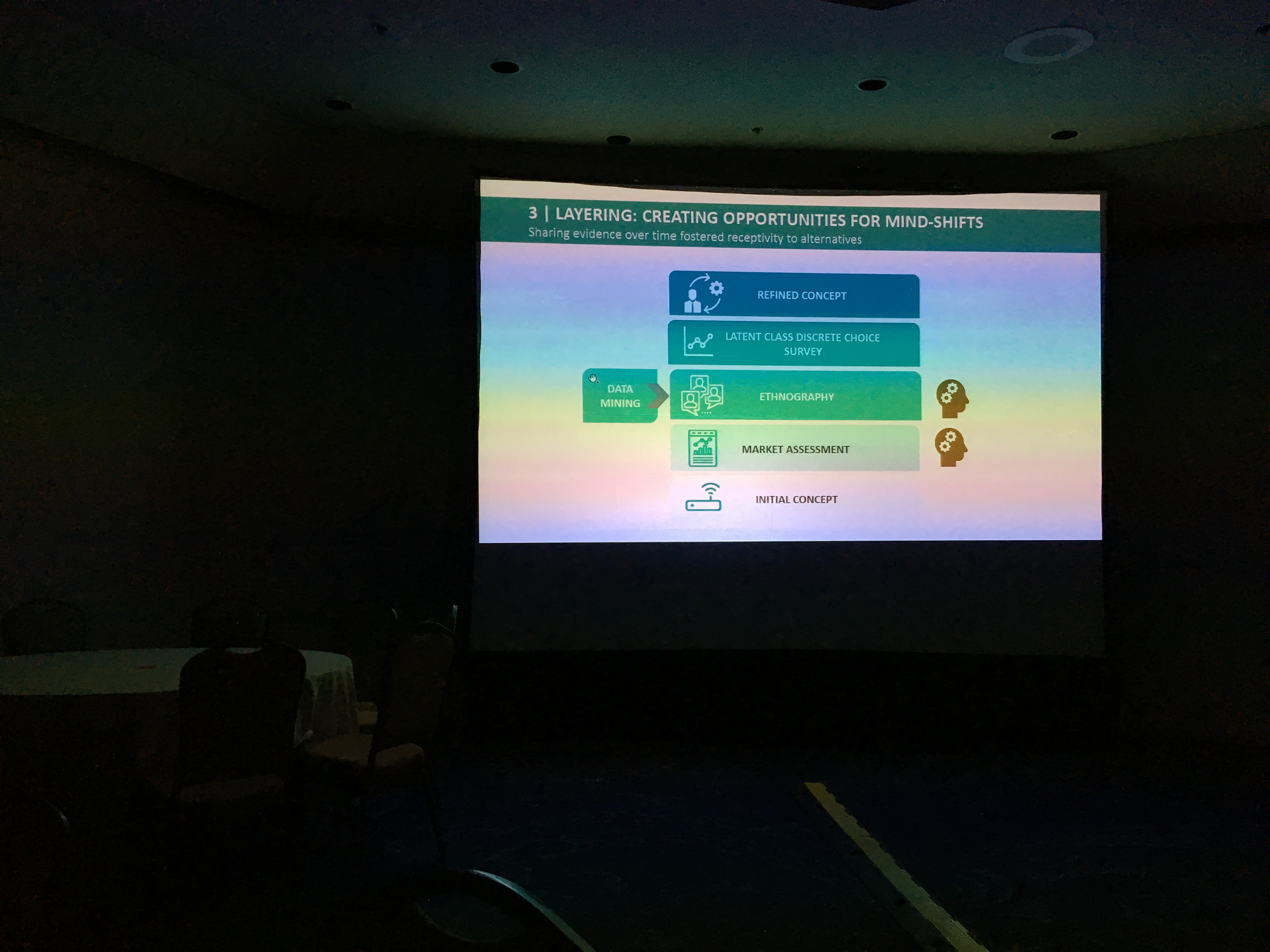

The project wasn’t really an open-ended question about ‘what would work best?’ But this doesn’t mean that the ethnographic methods were not useful - it still helped in answering the question of ‘would this work?’ (and our answer was ‘a qualified maybe’) This shows that ethnography can be a part of a layered process.

Q: How, when doing this sort of work with stakeholders, do you stop people from jumping to conclusions?

A: Helps to frame it correctly from the start. Also, helps that we weren’t making wholesale recommendations from the start. Means you can introduce bits of insights gradually.

ReHumanizing Hospital Satisfaction Data: Text Analysis, the Lifeworld, and Contesting Stakeholders’ Beliefs in Evidence

Julia Wignall & Dwight Barry · Seattle Children’s Hospital

[Sorry - missesd the beginning of this]

Issues around staff communication around intensive care, long surgery procedures, etc - The capturing of the feedback of all this gets reduced into a single patient satisfaction score.

Wrinkle is that Medicaid and funding will soon be tied to this one patient satisfaction score.

The challenge:

Techniques to tackle this:

- End user reading: getting stakeholders and stakeholders to actually read the verbatim feedback from. Most leaders can readily identify the problem areas, but when we spoke to them they mostly felt they cannot do anything about it. THey mainly wanted us to thelp them bring evidence to light so they can obtain the high level support they need.

We did further content analysis but really struggled to get from their to concrete recommendations. Most feedback mainly just said they felt wait times were too long. Content analysis alone was not enough

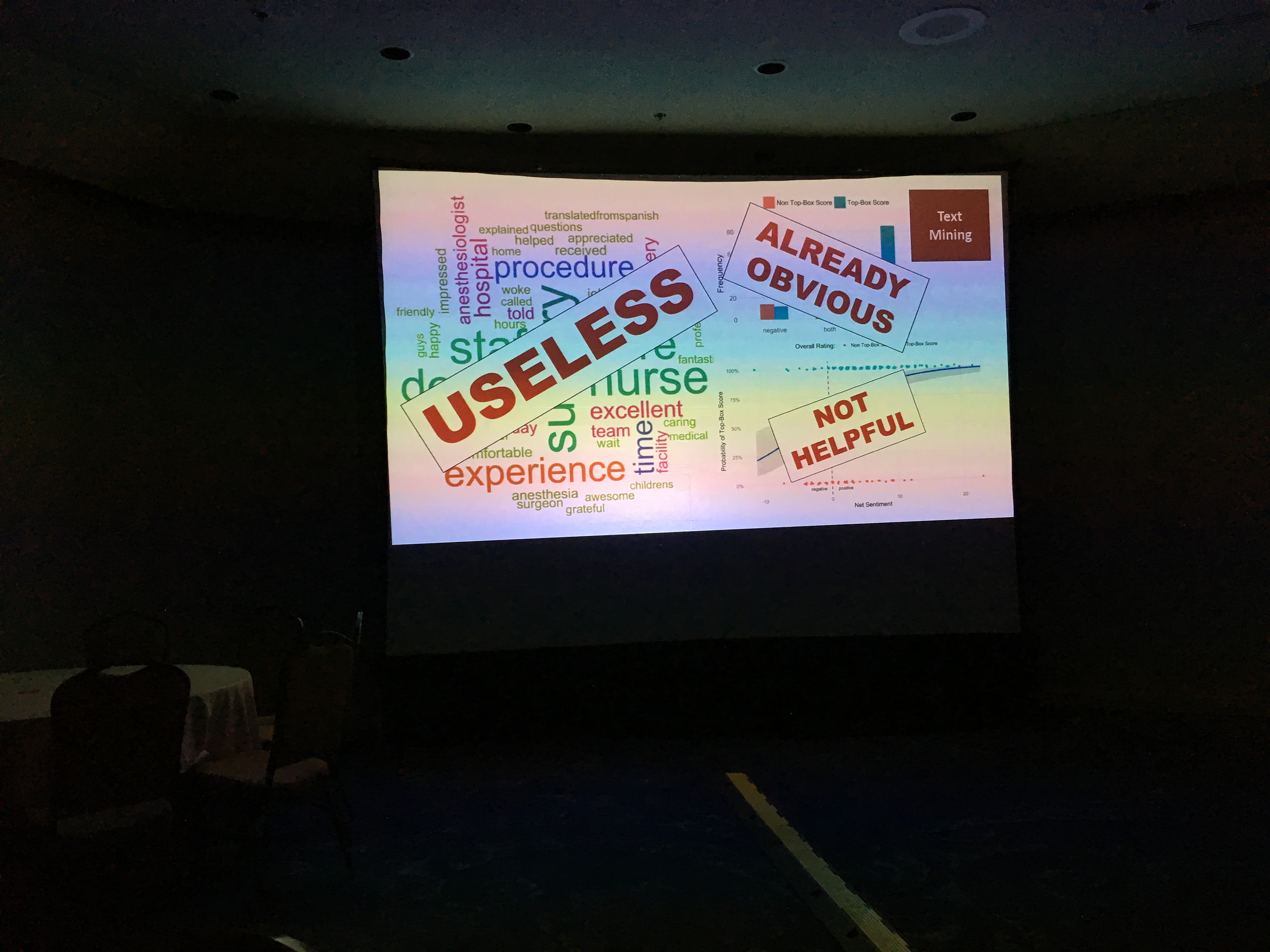

We tried different types and methods of text mining. But…

We expected this. Most of these things cannot provide meaning.

That led us to Ethnography. We wanted to bridge the gap between survey scores and patients’ stories.

Theory of the ‘life world’ by Husserl. Patients are individuals with diverse and often serious needs. Like them, we are trying to find our place within this - We operate in between information and innovation needs, and change and stability needs.

The KPIs lke satisfaction are not going to go away, but in fact will likely rise in importance. [One pushback against that is] Qualitative and Quantitative researchers coming together to push back aginst bad data requests.

Q: How did an anthropologist and a data scientist pair up? A: Worked in different buildings. Connected over conversations around ethics of data. and over time realised they were getting similar requests. So over time had more questions around how we better understand each other’s processes and use our research to better effect.

Q: How to deliver bad news to clients? A: Highlight what has worked. So, even though generally the feedback was not so awesome, this particular bit was really good!

Communicating: Evidence, Big Data, and Empathy

Physicalizations of Big Data in Ethnographic Contexts

Jacob Buur, Christina Fyhn & Sara Said Mosleh · University of Southern Denmark

The idea that you can create material objects that help inform and make sense of data. Two case studies: university library and chronic patients

3D printed curves of noice and CO2. Underlying question: how does indoor climate influence what library users would do?

Things that might not be immediately obvious to people: entrance and hallways have lots of noise and lots of people passing through but low CO2. But study areas are quiet but have high CO2 concentration.

Touching data has a special quality to it. It provides ownership - people suddenly start talking about ‘my data’

Created laser-cut graphs of patients levels of pain over time.

This allowed juxtaposition of data and meaning was created when people tried to put data sets (i.e. the laser cut graphs) next to eah other in different ways.

Physical bar graphs of customer queries:

The material (i.e. the physical bar charts)also becomes a tool for people who are not familiar with how the library worked to ask questions.

Four conclusions from the case studies:

-

There’s a quality to touching data that enriches conversations

-

Juxtaposing data shifts perspecives

-

Stacking data imgines what could be

-

Co-constructing data provides depth

Q: What experiments would you like to see from design anthropologists working with data visualisation? A: Data tinkering - experiments in more creative ways to express and visualise data.

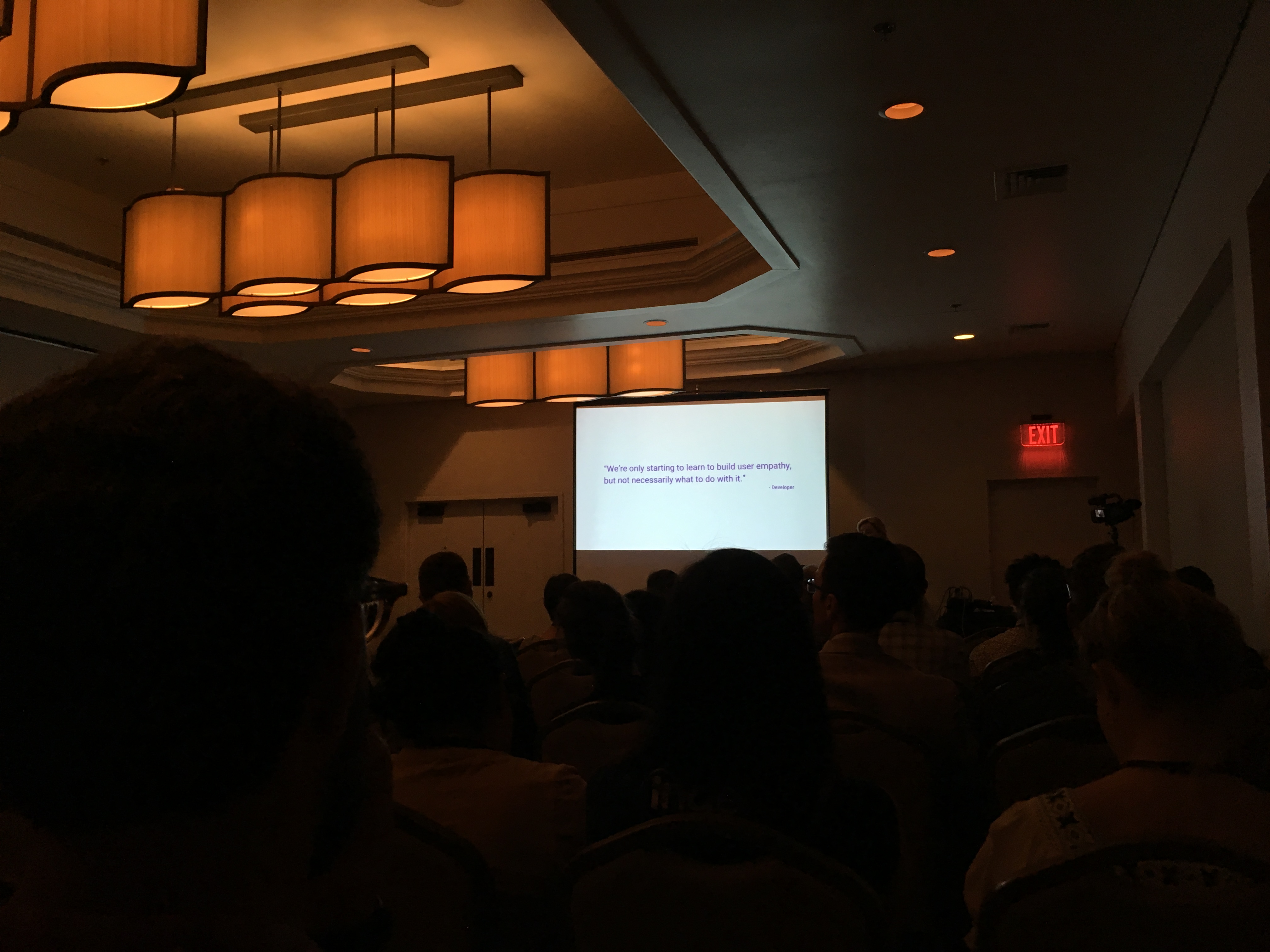

Empathy Is Not Evidence: How We’re Clouding Our Decisions through Emotional Biases

Rachel Robertson (@r_robertson) & Penny Allen (@penny_allen) · Shopify

4 traps of commodifying emapthy.

Ways to develop empathy for merchants on shopify: Site visits, shadowing customer service calls, highlighting their stories at company meetings, but…

Beyond building user empathy, what to do with it?

People’s capacity for empathy can be affected in different ways, including by scale.

Empathy is not evidence, and not good for direct decision making

Found 4 traps:

- Creating fake empathy.

Found this trap in empathy-building exercises, such as getting employees at Shopify to ‘start their own store’ (employees bring different context into this: they know the platform really well and aren’t relying on the shop to succeed to suppor thier livelihood)

‘Pretending is not the same as being a user’

- Unbalanced use of empathy

For example: Shopify created cards that congratulate merchants on milestones that were actually really stressful for them.

Lack of deep understanding is a lack of empathy

- Empathy to force decision-making

In the absence of enough information, everyone says things like ‘as a user I would do x’, or talk about the problems of just one merchant.

This could flip the decision-making process upside down, (or allow people to invoke empathy to subvert the decision-making process)

- Superficial empathy for show

i.e. When empathy is used only for show or in the service of confirmation bias.

Empathy is not evidence, it’s a driver to seek evidence.

How to apply these learnings?

One example - creating a decision tree for employees coming back from a merchant visit.

Q: Researchers sometimes asked to do ‘leadership immersions’ to help stakeholders develop empathy. What to do in those situations?

A: Have methodological practices in place and use them. Decouple the caring from when decisions are made. You want people to connect and care about users, but not necessarily when they’re trying to make decisions that should take into account lots of different pieces of information

Q: Has empathy replaced insight?

A: yes, a part of what the traps try to highlight is when people rely on the feeling of empathy [emotional empathy?] when there isn’t insight [cognitive empathy?]

Q: Relation between emotion and methodology.

A: Often the way data is represented suggests that it is objective, finite and done. For us, by using physicalisation, we take away the objectivity of it all and allows participants to express the subjectivity [in their interpretation and use of data]

Q: With data physicalisation - what if people don’t understand how to read graphs? What sense-making is really happening when they don’t undestand the underlying data?

A: A concern but this becomes really different when we ask people co-create the physical data representations, since it is their own experiences they are ‘mapping’ / creating visualisations of.

Ethnographic film

Questions to consider: In what ways do visuals serve as evidence in our work? Wht rules should participants play in creating and using sound and imagery? How do aesthetic choices back visual evidence?

Helping People Heal

by Rebbekah Park, ReD Associates & Emily Preston, Idea Couture

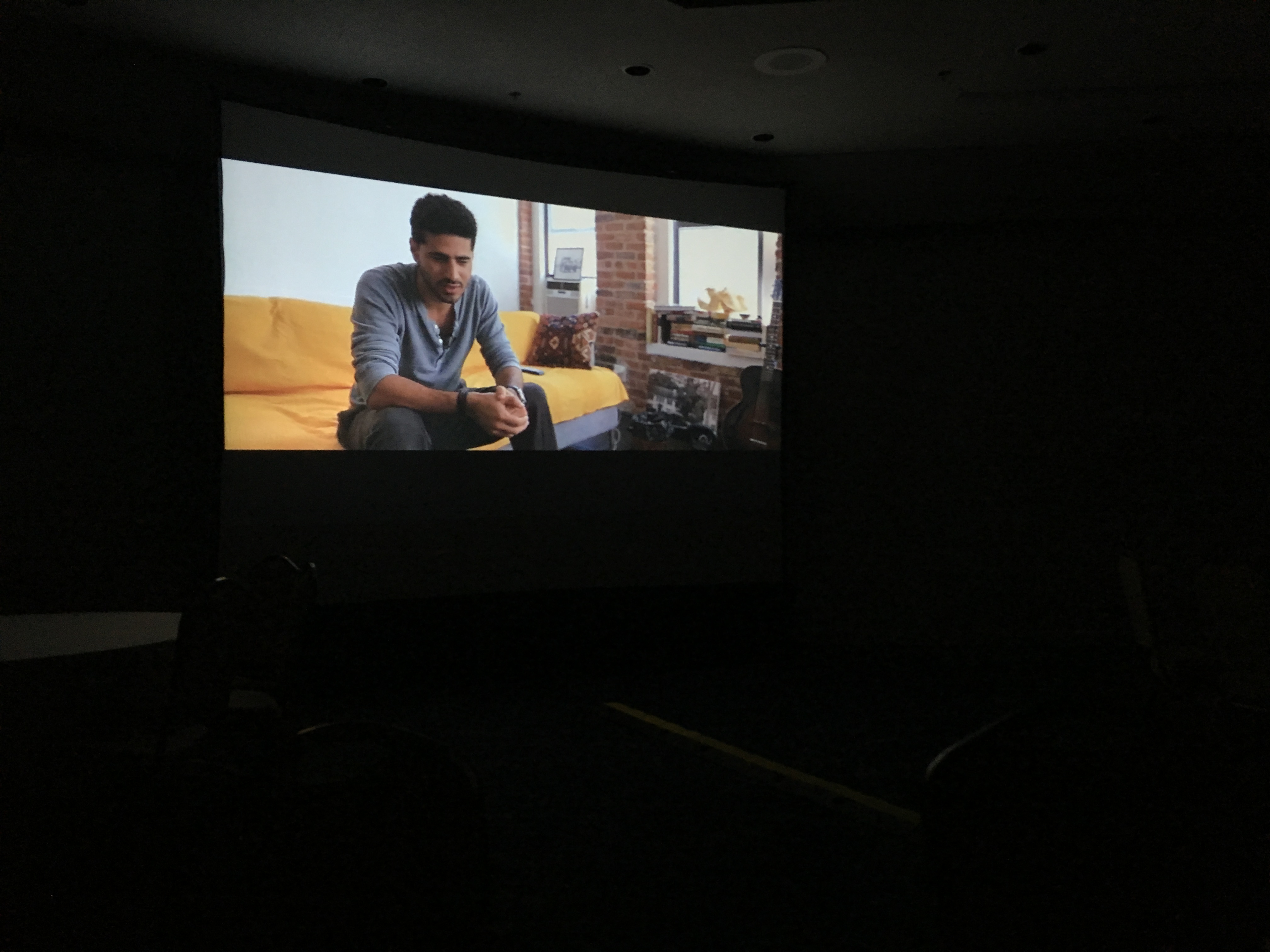

A documentary-style short film exploring how people in the United States heal themselves once they leave the doctor’s office. This film is based on in-depth field research and illustrates how healing depends on the alignment between what doctors expect from patients, and what people actually do in their everyday lives. Exploring and entering the lives of three individuals, Helping People Heal reveals the ways that people put their recommended treatments into practice—and why these personalized applications achieve better health outcomes beyond simply doing what the doctor ordered.

Six month ethongraphic study on healing.

film captues soties of three individuals

Steve: developed nerve compression in foot.

“The opinion of the doctors was that if anything hurts, it needs to be eradicated. Pain is not something you have to live with for an extra minute if it can be resolved?”

But he thought more about risk and what happens if something goes wrong that stops him from fulfilling his duties as a father

Susan and Tray:

“We’re as one… it’s not you going to the doctor, is we’re going to the doctors”

“I try to write something every day. Once you share, you’re healing by helping others”

Tal:

Been a diabetic since 2008. had started to count carbs - “It’s a very limited skill. Give me a plate of food I can probably tell you within 10-15 percent how many carbs are in it”

“I think it’s really important that people understand on a physiological level what’s going on with their body and have a conversation about that.”

Q: The difference in the participants’ view of evidence vs how it was represented in the film

A: We saw this film as a piece of ethnography. A way of telling the ethnography through the story of these three people. The evidence came from them and our choices (in storytelling) were led by them.

Q: To what degree do you produce these films taking into consideration the specific impact it can have on product decisions vs creating empathy with decision makers?

A: The film was not make in the context of an ethnographic research for a product. So instead of using it to create design parameters / influence product decisions, it was to broaden people’s perspective, humanising data, etc.

Q: Role and presence of the ethnographer

A: Feeling is that audience really doesn’t care about the ethnographer. Want audience to go into their world [through watching the film].

However, it could sometimes work - showing the process could help give a sense of authenticity

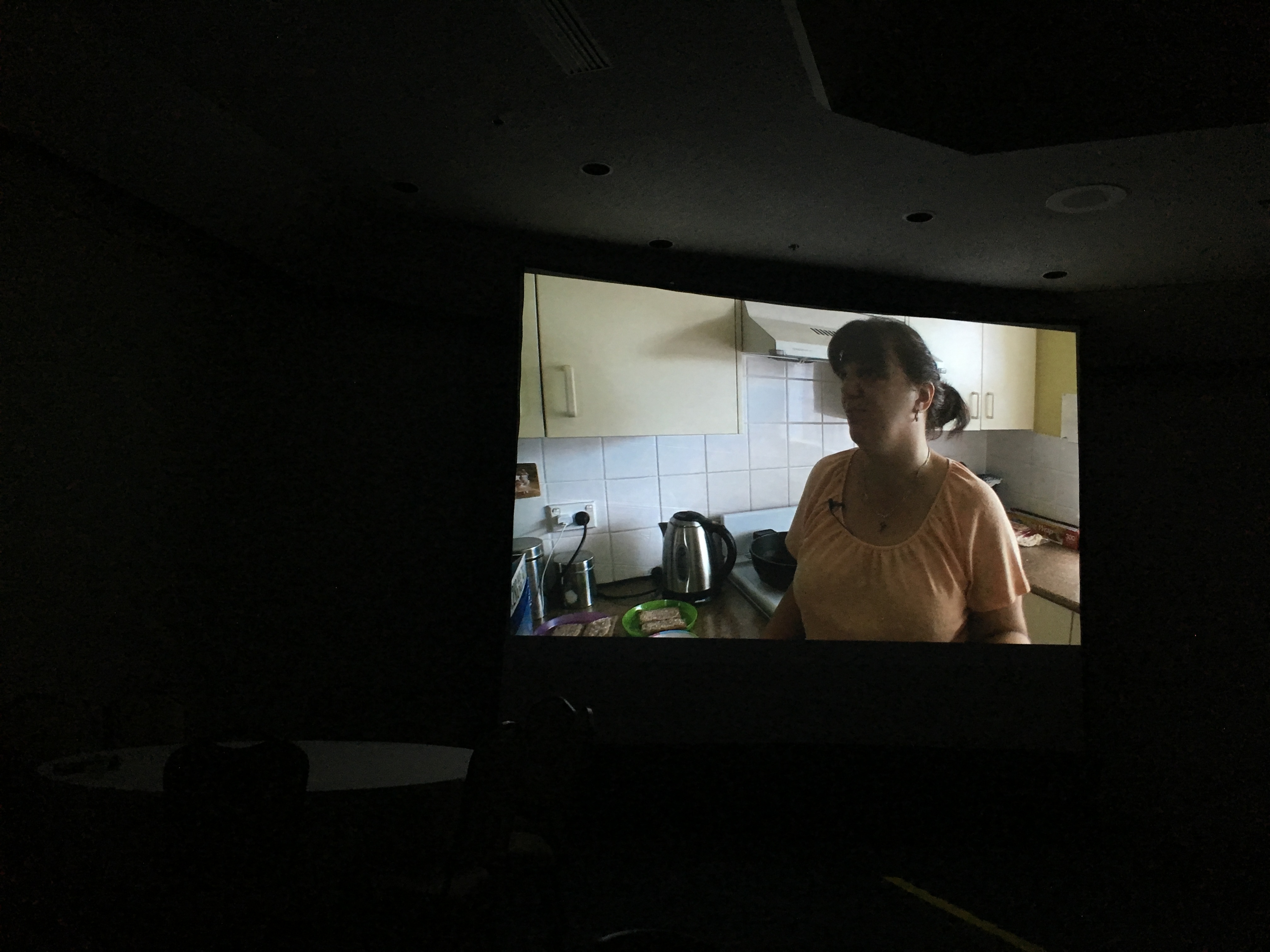

Tracey’s Struggle

by Shelley O’Neil & Charlie Cochrane, Jump the Fence

Despite the ‘foodie’ reputation perpetuated by reality TV, cooking shows, and food blogs, many Australians struggle with eating healthy food. MasterFoods brand has been a household name in Australian supermarket groceries for 70 years and have a 2020 brand ambition to help all Australians enjoy the rewards that good food can bring. So they asked Jump the Fence to conduct an ethnographic study to understand people with challenges around physical access, time, money, and skill with food. Tracey from Southwest Sydney is one of five people the study focused on. Tracey’s welcoming generosity and honesty are profound and reveal the complex layers of psychological, cultural and situational barriers she has to eating well.

“Trying to find her [Matilda] something to eat in the morning is really difficult. Used to be eggs” but now she doesn’t like anything

“I’m terrible with just chucking packets of snacks at them. but they’re cheap”

“I’m shattered. I’ve had it”.

“I”m back in a situation that I tried to get away from as a kid”

Today I didn’t have anything during the day. I didn’t have time at work…when the kids aren’t here, I won’t leave that couch.

“I was a fitness instructors in my twenties, so I know the difference between good eating and bad eating.”

Debt plays a big role.

“It’s about that balancing act. It’s continual.”

Q: What’s the connection between the evidence shown in the film and the actions that come from it

A: This was for a food company (Masterfood). They had already made a decision to do the campaign. But the research helped orient the campaign away from being about food specifically and more around the social context of food.

Q: To what degree do you produce these films taking into consideration the specific impact it can have on product decisions vs creating empathy with decision makers?

A: They go hand in hand. an effective way to have impact on product decisions is to help create empathy.

Q: Role and presence of the ethnographer

A: A really important nad pwoerful part of video ethnography is seeing the participants interact with their environment and with each other. Visually, the ethnographer doesn’t belong in that [milieux]. The audience understands from looking at the film that the ethnographer is there, but doesn’t mean you need to show it visually.

Ethnographic films are a construct, and so the question is, whether having the ethnographer in the film - does it help build that construct of the subject’s life?

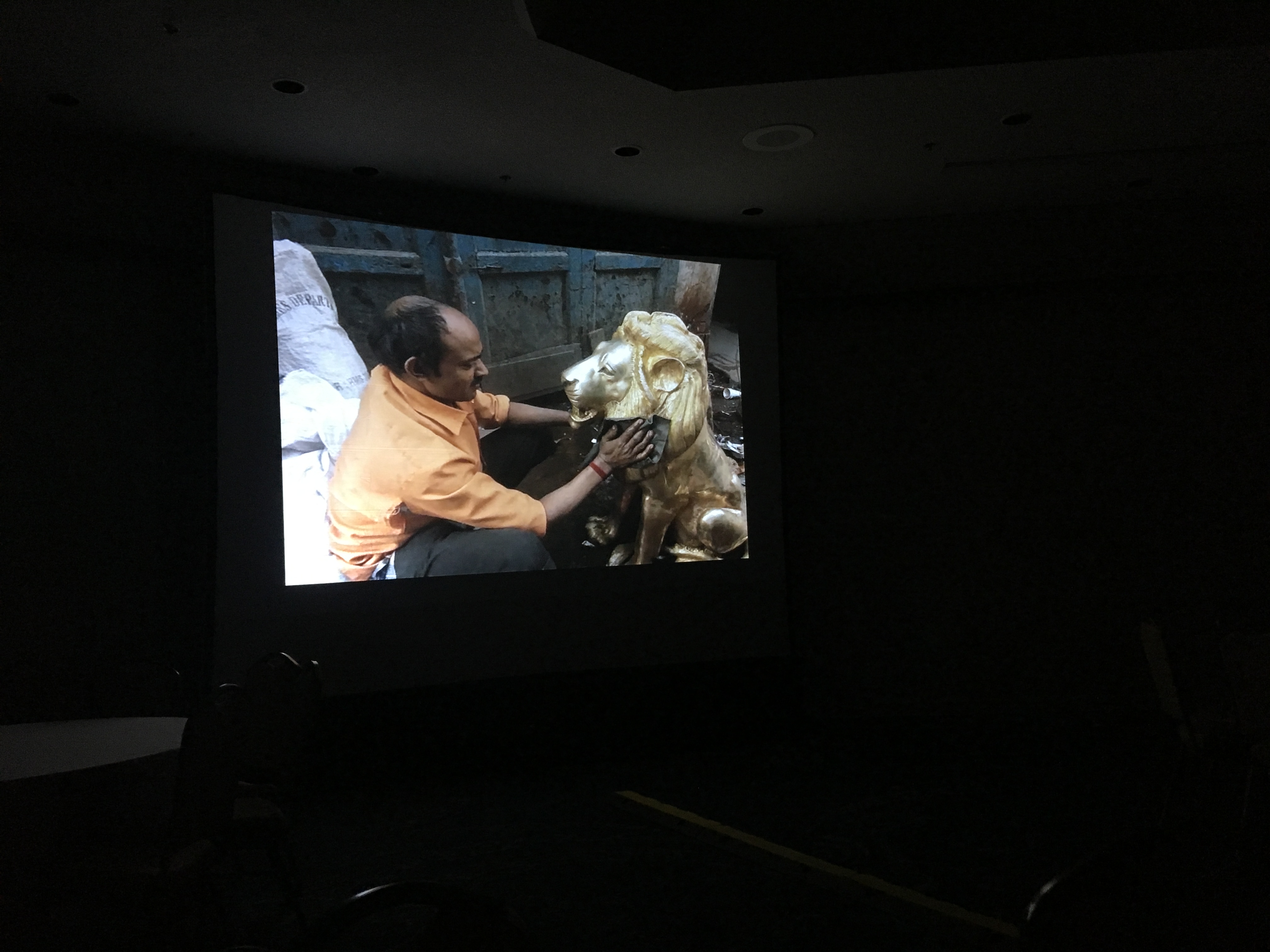

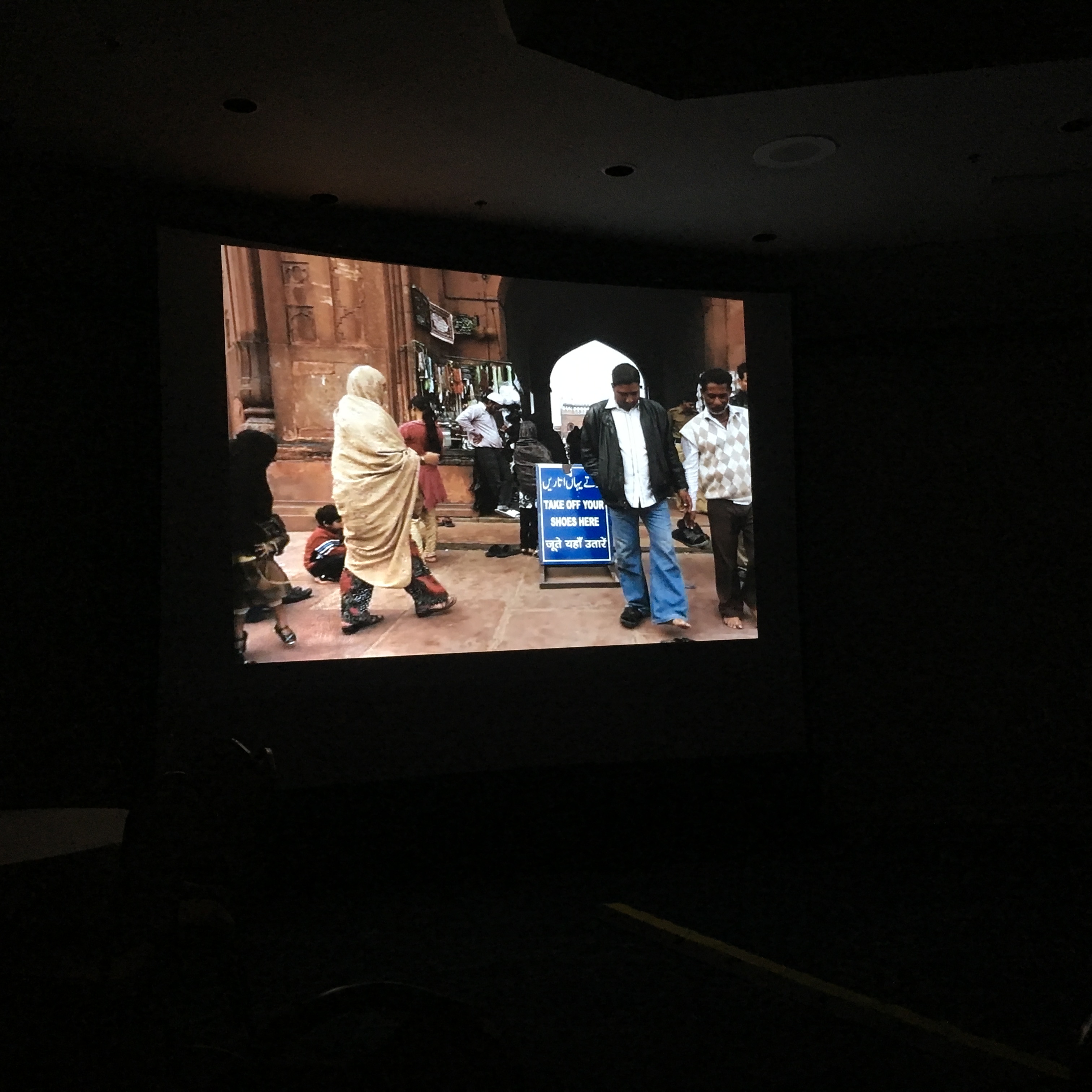

Seeing Double

by Karl Mendonca, Amazon Music

Dekho, Purani Dilli (Seeing Double) is an essayistic film that illustrates the experiential and contextual nature of ethnography, while reflecting on cultural predispositions that often frame ways of seeing and knowing. The film was produced as part of a design conference in Delhi, where conversations centered on ‘modernizing’ traditional modes of production, distribution and the object itself. My goal was to question a peculiar narrative of modernity and development that positioned design and digital technology as an answer to longstanding social, cultural and political relations. Working in the tradition of structuralist film making, the film is composed as a series of encounters in Old Delhi, where object and people play the role of interlocutors that prompt a turn to history and a deeper engagement with place. As an evidentiary form, the film is an inversion of the typical ‘deliverable’ serving as a critique of accelerated design culture and a meditation on the critical lens ethnography can provide.

Work. Labour. Capital?

Perspective

Networks. Assemblages. Palimpsests

Q: In a world where we are left to disern for our own real vs fake, what’s the role of ethnographic film?

A: Opacity. Instead of always driving towards goals and

Q: Why was the choice made to have the dream-like quality?

A: We had a day to go into the city. Where does the history of Old Delhi go? Where do we fit into all of that? Dream-like quality - play with time and temporality; make time a character.

Q: The intermission. Why?

A: The film is part-ethnographic. As a text, it does not compute. It doesn’t deliver an insight in a particular way. I wanted to make a film that would travel and that I could use it in a different way - almost as an artistic piece with reflexivity. It was part of a design conference - no one was paying for it so I could make an ethnographic music video.

A (from Shelley O’Neil & Charlie Cochrane): They’re all films so we put them togehter. But in other ways (intention, purpose, etc) they are completely different. It’s called a film now but it wasn’t when it was made. It’s being shown out of context now, and in the context of the work we were doing, artistry is of low consideration. There’ll be bad shots, out of focus shots, etc. Maintaining integrity of the data, evidence and the story is the most important thing.